TORONTO (Jan. 25) — Stories. Oh so many. And, they keep coming back when I reflect on my 23 years in radio.

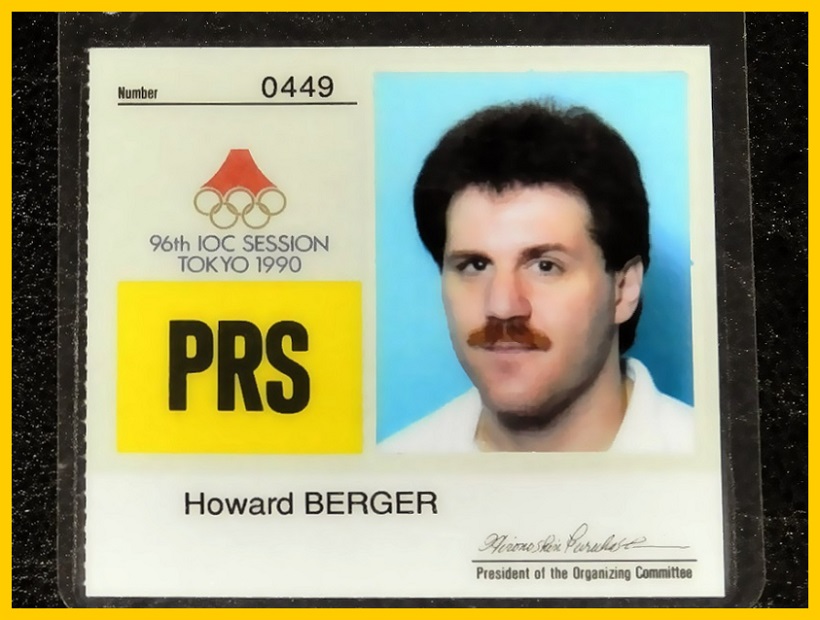

Such as the trip to Tokyo in September 1990 to cover the 96th Session of the International Olympic Committee, a three–day conference that would determine which city hosted the 1996 Summer Olympics. Toronto was among the six candidates along with Atlanta, Athens, Melbourne, Belgrade and Manchester. It was, by far, the biggest assignment of my 2½–year tenure at CJCL AM–1430; and still two years before we became the first all–sports radio station in Canada. I flew to San Francisco on Sep. 13, 1990 and switched aircraft for the 11–hour, trans–Pacific journey to Narita Airport, 60 kilometers east of central Tokyo. It was Thursday morning in Toronto when I left… and late–Friday afternoon upon arriving in Japan; Tokyo being 13 hours ahead of Eastern Standard Time in North America. So organized and efficient are the Japanese people that I was met at the Arrivals gate and ushered immediately to a dizzying array of 100 or so coach–type buses in a neighboring parking lot. A tiny young woman with a radiant smile pointed me to the correct vehicle and bowed. Less than an hour later, I checked into the smallest hotel room of my life, with a single bed and just enough room to swing my feet off the mattress and onto the floor without hitting the adjacent wall. I remember running into Brian Williams the next morning; he covered the event for CBC Television. “My walk–in closet at home is bigger than the hotel room they booked for me,” he griped.

On the second afternoon of the trip, another bus took media members to the NHK Theater, a typical, Massey Hall–type music venue that hosted the opening ceremony for the IOC Session. The Emperor of Japan, among others, welcomed everyone to the country and a wonderful orchestra entertained the audience. Afterward, we gathered outside the theater with hundreds of people for our bus ride back to the hotel. The Toronto contingent was led by then–Mayor Art Eggleton and former Metro Chairman Paul Godfrey. I spoke briefly with them. Our city’s bid to host the ’96 Summer Games had been organized by Paul Henderson — not the famous hockey player, but a former Olympic sailor. A member of Henderson’s staff grabbed my arm and ushered me a few feet to the left, where Princess Anne, the daughter of Queen Elizabeth, was chatting with a group of admirers. Princess Anne was an IOC member and delegate from the United Kingdom. She would cast a vote for the ’96 Games and was obviously on hand to support the bid from Manchester. When she finished talking, the Henderson staffer introduced me to her. I politely extended my hand with a slight bow. Princess Anne did not extend hers. Rather, she cast me a withering glance and turned back — her nose in the air — to the previous group of admirers. I looked at the staff member as if to say “now what?” Somewhat embarrassed, he shrugged and we walked toward our bus.

THE MEDIA CREDENTIAL I WORE WHEN PRINCESS ANNE SNEERED AT ME.

Later that night, I was driven to the NHK Studio for a live radio hit back to Toronto. With the time difference, everything was ass–backward. At night, I would go on the CJCL morning show; in the morning, I’d appear on Prime Time Sports, with Bob McCown. For this appearance, I was set up at a microphone in a large, sound–proof room. Minutes later, in my head–set, I could hear our morning crew, led by Keith Rich and Maple Leafs broadcaster Joe Bowen. I chatted about the bid process, whereupon Keith — our morning host when I started at the station in May 1988 — asked if I had any stories to relate. Immediately, I began telling about my discourteous encounter, several hours earlier, with Princess Anne… to whom I referred as the “snot–rag daughter of Queen Lizzy.” After a brief and awkward pause, Rich and Bowen broke up laughing. The Japanese engineer behind the glass, fluent in English, looked on, his mouth agape. “Tell us how you really feel, Howie,” Joe chuckled as we wrapped up the segment.

A driver took me back to the hotel, where I grabbed a bite of supper then went up to my room, dog–tired after a 16–hour work day. As I began to doze, the phone rang next to my bed. It was Allan Davis, the network coordinator for Telemedia Sports and the man who made the decision for me to cover the Tokyo event (Allan is now the Program Director at WGR–550, the all–sports radio station in Buffalo). When I picked up the receiver, all I could hear was a person chuckling. For like 15 seconds. At first, I thought it was a crank call, but Allan soon got a hold of himself and read me his version of the riot act. “We’ve all been belly laughing, back here, over your description of Princess Anne,” he said. “But, next time, do you think you could be a bit more delicate? I’ve taken a half–dozen calls from Royal watchers who want your head. And, mine.” We laughed some more. “Sorry Al, it was the first thing that came to mind. I couldn’t help myself. Hopefully, you won’t hear from the Lieutenant–Governor.”

Postscript: Atlanta won the bid for the 1996 Summer Olympics.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

A similar “admonition” came from Program Director Nelson Millman a few years later. I was in studio talking about the Toronto Blue Jays during the 1993 baseball season. By this time, we were an all–sports station. It was a Monday afternoon. The previous night, on ESPN’S Sunday Night Baseball, broadcasters Jon Miller and Joe Morgan were rather dismissive of the defending World Series champion, suggesting there was no way the Blue Jays could repeat (they were wrong). At some point, the telecast came to mind and I said, “… of course, if you listened to those two pecker–heads on ESPN last night, there’s no reason to watch the Blue Jays anymore.”

About ten minutes later, Nelson waved me into his office. “Look, you weren’t wrong about the ESPN thing, but there has to be some other way of describing the broadcasters. Pecker–heads. Are you out of your mind?”

I just grinned. Nelson rolled his eyes. End of discussion.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Steve Stavro didn’t like me. If Queen Lizzy’s foal gave me a dismissive glance, the former owner of the Maple Leafs shot me looks that could kill. Perhaps it had something to do with the number of times I called him a “cheapskate” on the air. Stavro followed Harold Ballard as the chief poobah of Maple Leaf Gardens Ltd. and ultimately took the company private. With public shareholders out of the way, he ran the business on the order of Knob Hill Farms, the successful “big box” grocery chain founded in 1951. In other words, as he saw fit. Burdened elsewhere by financial issues, Stavro’s Leafs, as with Ballard, operated on a strict budget. This extended to the annual period of unrestricted free agency in the NHL (prior to the salary cap), during which the Maple Leafs “couldn’t afford” to pursue the top names. Which, as a reporter covering the team on radio, I contended was utter nonsense… and frequently made myself known. Thus, the recurrent killer glance from the owner, particularly inside the hockey office on the second floor of Maple Leaf Gardens, where I would often wait for an audience with the general manager (Cliff Fletcher, then Mike Smith). Stavro would walk in and greet the secretaries with a pleasant smile. Then, he’d turn to me and the smile would instantly morph into the expression of someone who had smelled a bad fart.

Fast–forward to the afternoon of Sep. 11, 2001, hours after hijacked planes had been used as missiles against the World Trade Center in New York and The Pentagon outside Washington. I was scheduled to fly to St. John’s, Nfld. for the start of the Maple Leafs training camp. When U.S. and Canadian authorities agreed to shut down North American airspace, jetliners did not take off until late on Friday, more than 72 hours after the terrorist attacks. So, I went to St. John’s on Saturday morning for an exhibition game, that night, between the Leafs and Montreal at the new Mile One Arena. Using an upgrade certificate, I sat in Executive Class on Air Canada, in Row 2 of an Airbus–320, directly in front of Stavro, his wife (Sally), Leafs’ president Ken Dryden and general counsel Brian Bellmore. They were stretched across the four seats of Row 3. Dryden and Bellmore acknowledged me; Stavro did not.

At some point during the three–hour flight — and, please understood this could only happen to Howard Berger — I awoke from a brief nap and headed toward the lavatory behind the flight deck. The little lever indicating occupancy was green. So, I opened the door… and there stood Steve Stavro, his drawers on the ground, leisurely emptying his bladder. Dumbfounded and horror–struck, I was gazing at the bare ass of the Maple Leafs owner. Instinctively, Stavro looked over his shoulder, though not far enough to see me. “Oh, geez, sorry,” I mumbled while gently closing the door. I turned and walked back to the cabin, shaking my head. Dryden and Bellmore — having witnessed the scene — were laughing uproariously. “Only me, Ken,” I said before slinking back into my chair.

Stavro returned a few moments later, thankfully oblivious to the culprit.

After arriving in St. John’s, I could see wide–body aircraft lining the tarmac from all parts of Europe and Asia — planes that were ordered to land at the nearest airport the previous Tuesday. So packed was the terminal building that we waited outside in a parking lot for our luggage to be delivered on a truck. The suitcases were placed on the ground. I was with Ken Campbell of the Toronto Star. After fetching my bag, Ken and I were about to look for a taxi when I heard someone yell my name. I looked up and noticed Stavro — his head poking above the roof of another cab. “Berger, do you guys have a ride downtown?” asked the Maple Leafs owner.

“Is Stavro talking to me, Ken?”

“I don’t see any other Berger here,” replied Campbell.

“Yes, Mr. Stavro, we do. Thanks for asking,” I yelled, bewildered.

Ken and I walked to a vacant taxi and loaded our bags in the trunk. “Where did that come from?” I asked, as the driver pulled away. “Stavro hasn’t said a word to me in his entire life. All he does is shoot me dirty looks.”

“Do you blame him?” replied Ken, laughing.

We arrived 15 minutes later at the Delta Hotel, across from St. John’s Harbor. I walked into the lobby and was startled to see dozens of people sprawled across the floor with blankets and pillows. There likely weren’t enough hotel rooms in the entire Maritime provinces for all the displaced passengers of 9–11. I figured the Delta couldn’t possibly have saved my room, even if I had booked it several weeks earlier. “No, Mr. Berger, we’ve honored all our reservations,” said the lady behind the front desk, turning to fetch a key. Just then, I felt a presence over my right shoulder. “Did you get your room okay, Berger?” asked Stavro, patting me on the back.

“Oh yes, thank you, I did, Mr. Stavro. Nice of you to inquire,” I said, now totally flummoxed.

The Coles Notes version is this: For some reason, which I am unaware of to this moment, Steve Stavro chose to act civilly toward me. From that day on, we had a very cordial relationship. I still found myself critical of his tight–fisted financial policy with players, but I was clearly more respectful in my reporting. Perhaps that was his strategy all along. If so, it worked. We had never engaged in a lengthy conversation until a day nearly four years later.

After covering the World Hockey Championships in May 2005, I boarded an Austrian Airways jet for the long flight from Vienna to Toronto. As part of our broadcast arrangement for the event, we were accorded Business Class seats on the Airbus–330. Situated one row back and to my left were Steve and Sally Stavro, who had also attended the tournament. We waved to each other. A few moments after taking off from Vienna International Airport, Stavro called out, “Berger, come here.” There was an empty seat next to him, in the aisleway. For the next two hours, I chatted amiably with the owner of the Toronto Maple Leafs; swapping stories while Mrs. Stavro had her nose in a book. I remember thinking how utterly inconceivable this would have been only a few years before.

During that conversation, I asked Stavro why the Leafs refused to sign Wayne Gretzky as a free agent in the summer of 1996. The Great One had finished the season with St. Louis after a trade from Los Angeles and was hoping to end his career with the team for which he grew up cheering. The most widely circulated story was that Stavro felt Gretzky could not add to the hockey club’s attendance, given the Leafs routinely sold out their games. Why, then, spend the money on a diminishing asset, even with No. 99’s appeal? “Not true,” the owner told me on that flight home from Vienna. “Fact is, Gretzky’s agent (Mike Barnett) asked for equity in our company. He wanted for Gretzky to own a part of the Leafs in order to sign with us. When we turned him down, the deal fell through.

“It had nothing to do with selling more seats.”

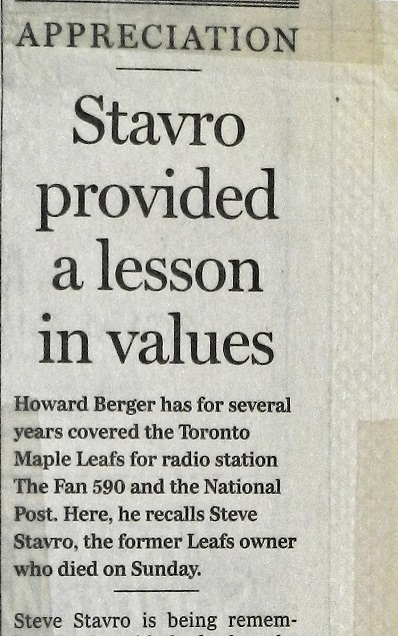

Stavro died just less than a year later, on Apr. 23, 2006. He was 79. By then, I had been covering Leafs road games for eight years on a freelance basis for the National Post, which did not travel with the team (I did radio and newspaper work during that time). Hours after Stavro died, I got a call from the editor–in–chief of the Post. “I’m told you got to know Stavro fairly well. Could you write an obituary article for our front page? In the first–person?”

It was an honor to be granted such a privilege.

And, proof that damaged relationships can somehow resolve.

EMAIL: HOWARDLBERGER@GMAIL.COM

Great story Howard….. keep it up; makes better reading than Leafs or Raptors results.