What Matthews has yet to do — what [Mike] Bossy accomplished — is transferring his regular season success to the playoffs.

— Steve Simmons, Toronto Sun, Apr. 5, 2022.

TORONTO (Apr. 7) — Yes, the numbers are astounding. There is literally no other way to put it. Forty seven goals in the past 48 games. A pace not witnessed in the National Hockey League since 1992–93 when Alexander Mogilny scored 76 goals in 77 games for the Buffalo Sabres. Prior to that, only Wayne Gretzky (twice), Brett Hull and Mario Lemieux lit the lamp so prolifically. Auston Matthews, therefore, finds himself in truly elite and historic company. He will vie, for a second time, to break the Maple Leafs franchise record of 54 goals, shared with Rick Vaive (who established the mark in 1981–82). Next opportunity is tonight at the American Airlines Center in Dallas.

Should he continue to score at nearly one goal per match, Auston will conclude the regular schedule with the ungodly total of 66. The most in one season since Lemieux put up 69 with the 1995–96 Pittsburgh Penguins.

After Apr. 29, however, Matthews’ scoring figure will revert to zero. And, the spotlight will sizzle as never before.

There can be no more excuses for a subpar playoff performance. Not after igniting his way amid such exclusive names as Gretzky, Lemieux, Hull, Mogilny, Phil Esposito, Teemu Selanne, Jari Kurri, Bernie Nicholls, Mike Bossy and Lanny McDonald, the only NHL players to score more than 65 goals in a season. Not after leading the Blue and White to a 10–3–2 record in the past 15 games, with signature triumphs over Tampa Bay, Boston, Florida and Carolina. A late–season stretch that brings to mind the two–month romp of February and March 1993 when Doug Gilmour — playing the best hockey of his life — paced the Leafs to an 18–3–3 mark in 24 games. Then proceeded to stockpile a franchise–record 35 points in 21 Stanley Cup matches as Toronto knocked off Detroit and St. Louis before famously losing to Gretzky and the Los Angeles Kings in Game 7 of the Conference final at Maple Leaf Gardens. This is the anticipated caliber of leadership that burdens Matthews with every goal he scores.

Only he can lift the playoff anvil off his shoulders. And, it absolutely must happen this spring.

The alternative is terribly unpleasant: being viewed as a fraud. Which will befall Matthews if he again wilts under the physical duress of Stanley Cup competition; if he repeats the blight of a year ago when he managed just one goal in the seven–game, opening–round collapse against Montreal. The truly great NHL skaters don’t merely show up for the playoffs; they prevail exponentially, getting better with each best–of–seven round. A trend foreign to the Maple Leafs since the consecutive gems turned in by Gilmour — 73 points over 39 games and six playoff series in 1993 and 1994. A level that is fully expected of Matthews in his upcoming sixth post–season appearance.

No longer can the Leafs; their fans and the horde of media that lionizes Matthews be content with a disappearing act and first–round elimination. Even if the Toronto playoff bar is set so remarkably low. Matthews will likely vie for the Hart Trophy this season with Jonathan Huberdeau and perhaps Johnny Gaudreau. If he isn’t in the “Heart” trophy conversation once the playoffs begin, all the fan and media fuss will have been for naught. It is Matthews’ time to not only step into the playoffs but to step up with his Stanley Cup peers. To be among the Conn Smythe Trophy candidates. To be talked about as much as Nikita Kucherov, Victor Hedman, Andrei Vasilevskiy and others of recent championship ilk. And, most critically, to show that he has another gear when physically challenged.

Matthews is plenty large enough (6–3, 220 pounds) to not only withstand the playoff slog, but to create havoc.

Still waiting to be answered is if he has the emotional composition to “toughen up” in the real NHL season.

The anvil becomes heavier with each goal scored between October and April.

HOW CAN IT BE 45 YEARS?

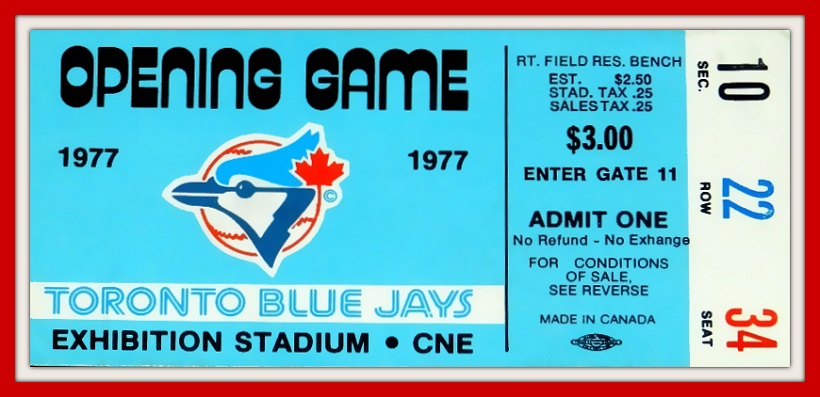

Oh, was it cold… like watching a baseball game in mid–January. Only this was Apr. 7 and unlike any such date in memory. The Toronto Blue Jays played their first Major League Baseball game 45 years ago this afternoon. Yes, I still have my ticket stub from the historic match (above) and I can easily recall the chill that overcame me (photo, below) long before the final out of a 9–5 Toronto win over the Chicago White Sox. The name Doug Ault still resonates in Blue Jays conversation for the pair of home runs he hit on that 1977 opening day. In an era long before all–sports TV, the game was carried nationally here in Canada by CBC — the late Don Chevrier (Dec. 29, 1937–Dec. 17, 2007) called the play alongside former New York Yankees shortstop (and NBC baseball commentator) Tony Kubek (b. Oct. 12, 1935). The stadium public–address announcer was some guy named Bob McCown.

The bone–chill kept me at the ballpark until the end of the fifth inning. At which point I could take no more. I hustled back uptown for a quick bite of supper, then turned around and went south again, to Maple Leaf Gardens, where the Leafs and Pittsburgh Penguins were contesting Game 2 of a best–of–three preliminary playoff round. Facing elimination after losing the opener on home ice, the Penguins bolted to a 3–0 lead in the first period; withstood a Toronto comeback to knot the score, then put the match on ice, 6–3, in the third period.

All of that 4½ decades ago today. Hard to fathom.

EMAIL: HOWARDLBERGER@GMAIL.COM

I was fortunate enough to be at the game with my parents and have the three ticket stubs, two programs and newspaper clippings from the day of and day after the game. I remember pregame a White Sox player wearing catcher shin guards under his feet as skis and used two bats as poles and cross country skied in front of the dugout.

Hey Howard – can’t believe it has been 45 years! I was there that day too – still have the program and my ticket stub. It was cold and damp and great fun. I also recall that as the crowd dwindled, a couple of kids started collecting empty bottles and lining them up along the top row of the right field bleachers. There were so many bottles that the collection stretched across several sections (and rows), despite stern warnings that bringing in alcohol was strictly prohibited.