TORONTO (May 11) — It was two months ago today that I had a standing invitation from the hockey author, Kevin Shea, to attend the following night’s game at Scotiabank Arena between the Toronto Maple Leafs and Nashville Predators — a first opportunity in nearly three years to watch the Leafs play, live. Such activity had dominated my years of employment at The FAN–590 between 1993 and 2010. But, my second career, as a funeral director’s assistant at Benjamin’s Park Memorial Chapel, restricted hockey viewing to television.

So, I truly looked forward to attending the Toronto–Nashville game with my pal, Kevin.

That night, however, the National Basketball Association abruptly announced suspension of activity after one of its players tested positive for COVID–19. A source informed me the National Hockey League would follow suit “by noon the next day”… and I dropped Kevin an email suggesting the Leafs–Predators match would be postponed. It wasn’t until 2 p.m. the following afternoon that Gary Bettman made the news official. By the end of Mar. 12, all of North American professional sport was mothballed amid the burgeoning coronavirus. Innumerable “plans” have since been formulated, but not a single hockey, baseball, basketball or soccer game has taken place. It is probable, here in Canada, that football will join the idle sporting list.

If you’re a fan of the Maple Leafs, and while, perhaps, yearning for hockey, the dominant memory of the club’s first 70 games should be one of disappointment. Though in decent shape to qualify for the playoffs a fourth consecutive year, the Leafs were a faraway third in the Atlantic Division with 81 points — 11 in back of Tampa Bay and 19 behind first–place Boston. Having scored 238 goals and yielded 227, Toronto stood a mediocre plus–11, nowhere near the plus–50 and plus–53 belonging to the Lightning and Bruins. The Florida Panthers, meanwhile, lurked three points in arrears of the Blue and White, with a game in hand. So, that berth in the Stanley Cup tournament was hardly guaranteed. With 36 wins, 10 fewer than last season, the Leafs had to virtually run the table in their final 12 matches to break the 100–point barrier for a third consecutive year. And, all of that despite the club’s nucleus of forwards performing at or above expectation:

AUSTON MATTHEWS had a career–high 47 goals (third in the NHL behind David Pastrnak and Alex Ovechkin, each with 48) and was (barring injury) about to become only the fourth player in Leafs history to reach the 50–goal plateau (joining Rick Vaive, Gary Leeman and Dave Andreychuk). He needed seven goals in the final 12 games to equal Vaive’s team record of 54 in one season, established in 1981–82.

MITCH MARNER left off with 67 points in 59 games (on pace for more than 80), having lost 11 matches to a high–ankle sprain suffered against Philadelphia, Nov. 9. He returned Dec. 4 and led the team with 51 assists when play stopped, the ninth–highest mark in the NHL. Clearly, and again, the club’s best all–round forward.

JOHN TAVARES was slowing, somewhat, at 30 years of age, but the captain still competed at a fairly elite level, with 26 goals and 60 points in 63 games. His minus–7 was a blight, nor was he going to come near his career–best 47–goal effort of last season. Nonetheless, he performed generally to expectation.

WILLIAM NYLANDER was playing his best hockey as a Leaf with a career–high 31 goals in 68 games. At 59 points, he was set to easily surpass his season–best total of 61, accumulated in 2016–17 and 2017–18. His nine powerplay goals were second on the team to Matthews’ 12. He was using his quick release effectively.

With the Big 4 up front contributing 120 goals and 146 assists for 266 points (a 66.5–point average), why were the Maple Leafs scuffling for most of the season? One reason, without question, was the long–term absence of No. 1 defenseman Morgan Rielly, who had just returned when the league shut down after a 23–game absence with a cracked bone in his foot. Neither had Morgan been healthy before the injury, contributing just three goals and 27 points in 46 games. That, after a Norris Trophy–caliber season last year in which he became the first Toronto defender since Borje Salming in 1979–80 to top the 70–point mark. Tyson Barrie paced the Leafs blue–line with a meager 39 points (and minus–7) in 70 games. Rielly, despite missing more than a quarter of the schedule, was next. So, production from the back end had diminished.

Given that prospects Rasmus Sandin (28 games with the Leafs) and Nick Robertson (55 goals with the OHL’s Peterborough Petes) are more–than–likely to play in the NHL — and that Toronto has signed the top–scoring defenseman from the Kontinental Hockey League, Mikko Lehtonen (49 points in 60 games with Jokerit–Helsinki) — general manager Kyle Dubas could assume a wait–and–see posture whenever play resumes. But, the questions remain: Where would the Leafs be if not for the 266 points from the Big 4 up front… and why had the club regressed in spite of such totals? Can Matthews, Marner, Tavares and Nylander increase their production? And, is it prudent to anticipate that Sandin and Lehtonen will perform effectively on the blue line, thereby improving an imbalanced roster and closing the enormous gap with Tampa Bay and Boston? That’s a lot to expect from six players… and the club, undoubtedly, remains too rich (in talent and salary) amid forwards. At some point, it will be in Toronto’s best interest to trade one of the aforementioned.

Tavares isn’t going anywhere, locked into his no–movement pact for another five years. Unloading Marner — irrespective of return — would be the sorriest move the Leafs could make since trading Lanny McDonald more than 40 years ago. That leaves Nylander and, yes, Matthews as candidates to help stabilize the roster.

Given his age (24) and scoring clip, Nylander’s cap–hit ($6,962,366) and term (three more years) are eminently movable. Trading Matthews, among the purest scorers in Leafs history, seems incomprehensible, but he’s not nearly the 200–foot player scouts expected in 2016 (or, that McDonald was) and he’ll be free to choose another NHL home in 2024–25; still just 27 years of age. So, again, the Leafs can hang onto their Big 4… and hope that Sandin and Lehtonen solidify the blue line (hope, of course, has failed to materialize since 1967). Or, Dubas could become bold and peddle one of Nylander or Matthews for a king’s ransom. I’m not suggesting that Alex Pietrangelo (St. Louis) or Drew Doughty (Los Angeles) would waive their movement restrictions, but either would brilliantly level the roster and enhance Toronto’s Stanley Cup aspiration.

What I do know is this: the Maple Leafs team we last saw, on Mar. 10 (and despite defeating Tampa Bay that night), isn’t nearly uniform enough to end the 53–year championship drought. And… Stanley Cup windows do not remain open indefinitely. That’s why Pietrangelo or Doughty (as two prominent examples), even at 30 years of age, would immeasurably complement the Blue and White. I favor, more than ever, utilizing the riches up front to balance the hockey club. Otherwise, the Cup famine continues. Indefinitely.

MY BOBBY ORR STORY — 50 YEARS AFTER “THE GOAL”

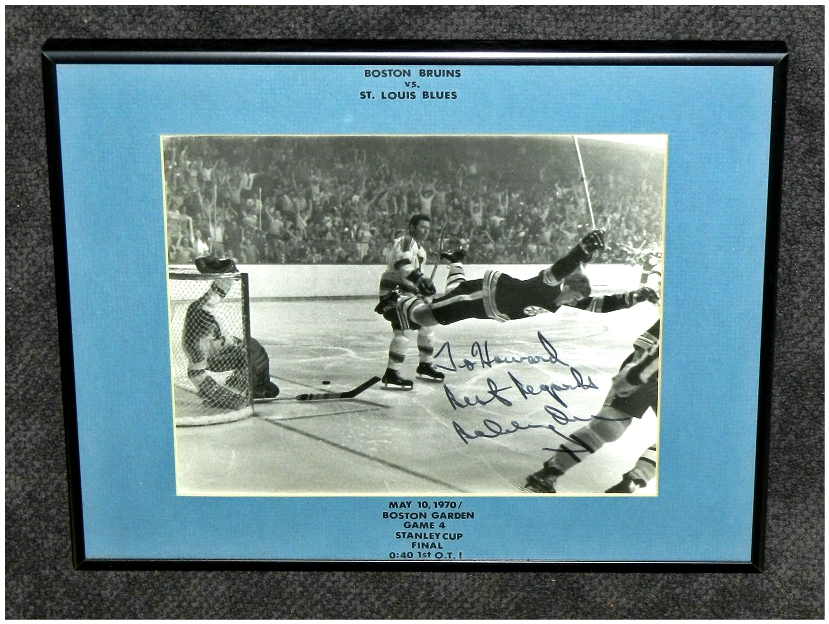

It was May 22, 1988 — a spectacular spring afternoon in Boston. Several hours before Game 3 of the Stanley Cup final between the Bruins and Edmonton Oilers. While strolling along the Faneuil Hall Marketplace, I came across an 8 x 10–inch cardboard copy of the iconic photo, snapped just more than 18 years earlier, that showed Bobby Orr, horizontal to the ice at Boston Garden, an instant after scoring on St. Louis goalie Glenn Hall, in overtime, to win the 1970 Stanley Cup. Thinking that Orr would likely be at the Garden for the Bruins–Oilers match that night, I purchased the photo, determined to have it signed. Arriving at the empty Garden 90 minutes before the game, I approached Ed Sandford in the main press box. Ed had been a left–winger with the Bruins, Detroit and Chicago from 1947–56. In 1988, he was the supervisor of off–ice officials for Bruins home games — 59 years old that night; today, he is 91. I showed Sandford the photo and wondered if he knew where Orr might be watching the game. Without hesitation, he said “come with me”.

I followed Ed along the last row of the steep upper–balcony that stretched the length of the ice on the east side of the Garden. We stopped near center–ice and Ed told me to “wait here”. A few moments later, I heard a person walking toward me in a private box slightly above my head. It was Bobby Orr, then 40 years of age. “Hi, Howard, nice to meet you,” he said, smiling and extending his right hand. “I think I’ve seen that photo before. Let me have it.” Seconds later, it re–emerged with the inscription, as seen above. “Enjoy the game tonight. I appreciate you coming over.” What I remember most about that remarkable moment is how Orr made me feel as if I’d known him all his life. I thanked him profusely and walked back to my press box seat with Sandford, whom I will also not forget for his kindness. Eight days later (May 30, 1988) I began my radio career at CJCL AM–1430 here in Toronto — to become, in September 1992, Canada’s first all–sports station.

While covering the Maple Leafs from 1993 to 2010, I had the privilege of getting to know Orr (currently a player agent) on a name–basis. Today, at 72 years of age and 50 years after scoring his legendary goal, Bobby receives this blog via e–mail… and apparently reads it when having difficulty falling asleep.🙂

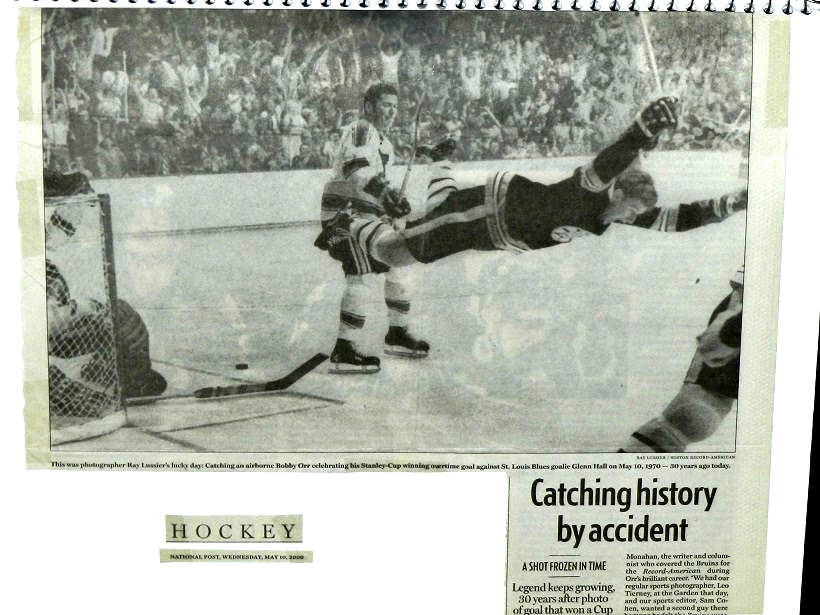

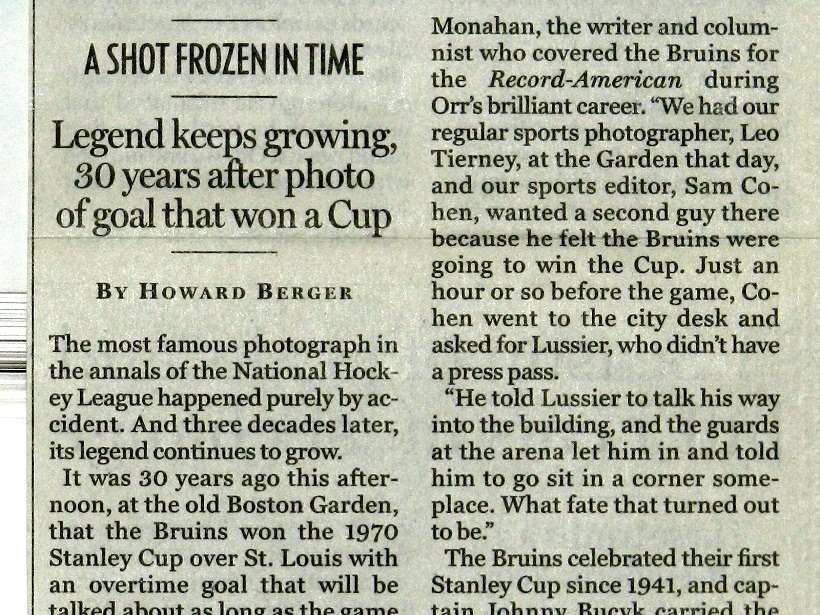

It has been stated that the 1970 Stanley Cup–winning goal would be remembered less fondly if not for Ray Lussier’s famous shot (above) of Orr taking flight, with an assist from St. Louis defenseman Noel Picard. The images, above and below, are from a story that I wrote for the National Post on May 10, 2000… 30 years after the goal. Clearly, the photo has immortalized that moment. But, would it transcend decades if, say, Wayne Carleton or Don Marcotte were soaring through the air? Both were members of the Bruins and Carleton — once a hot–shot Junior prospect here in Toronto — was on the ice and the first teammate to mob Orr after the defenseman landed. The question, of course, is rhetorical and silly. Orr makes the photo and always will. It was his season in 1969–70: the first defenseman to win the Art Ross Trophy, with 120 points (33 goals, 87 assists), 21 more than teammate Phil Esposito. Orr compiled 31 more assists than runner–up Esposito; only Espo, Stan Mikita (Chicago) and Frank Mahovlich (Detroit) scored more goals. It was the first of only three seasons in which Orr played every game for the Bruins. When doing so for the last time, in 1974–75, he again won the Art Ross Trophy. No other defenseman has come close (though Paul Coffey posed a reasonable likeness while skating with Wayne Gretzky and Co. in the mid–1980’s).

Some suggest Orr’s accomplishments were diminished by the caliber of play just three seasons after the NHL expanded from six to 12 teams. But, every player in the league had the same opportunity, so the argument is moot. Orr was not only the premier talent in hockey, but more lengths ahead of the second–best player (take your pick) than any figure in history, Gretzky included. That the Bruins captured their first Stanley Cup in 29 years is often lost amid Orr’s exploits, but the Hall–of–Fame defenseman would likely agree that his Boston team should have won three consecutive NHL championships. The following year’s club (1970–71) ranks among the best ever with a record of 57–14–7 for 121 points — a 22–point improvement and still seventh, all time, in the NHL. It scored 399 goals, 12 more than the most–prolific regular–season club: the 1976–77 Montreal Canadiens (132 points). Orr became the first player to record triple–digits in assists (102). Esposito scored 76 goals, demolishing Bobby Hull’s record of 58. Esposito, Orr, John Bucyk and Ken Hodge were the top four point–getters, a feat unequaled by even the great Oiler teams of Gretzky, Coffey Mark Messier, Jari Kurri and Glenn Anderson. But, the ’70–71 Bruins were startled in the opening round of the playoffs by rookie goalie Ken Dryden and the eventual Cup–champion Canadiens.

Boston rebounded to win the 1972 Stanley Cup (over the New York Rangers), led by Orr’s dazzling, Conn Smythe Trophy performance (24 points in 15 games). So, yes, it truly should have been a three–peat.

Somewhere in my condo locker, downstairs, I have a cassette–tape recording of Prime Time Sports from May 10, 1990, during which Bob McCown and Bill Watters conducted two interviews that commemorated the 20th anniversary of Orr’s goal. I produced the show and could have listened for hours. First, we had Derek Sanderson and Noel Picard on the line together. It was Sanderson’s pass from the corner that Orr slapped past Glenn Hall… and Picard, the veteran defenseman, that “helped” Orr take flight by flipping Bobby’s left skate with his stick. Sanderson and Picard, fierce combatants on the ice during their careers, needled one another and laughed heartily during the 15–minute segment. It was terrific radio. Orr then joined us for the final two segments, having listened to the repartee between Sanderson and Picard. McCown and Watters pulled off the interviews as only they could in the early years of the iconic radio program. I remember leaving the station on Holly St. that night with such a remarkable feeling of nostalgia.

All are still alive except for Picard, who died in Montreal on Sep. 6, 2017. He was 78.

EMAIL: HOWARDLBERGER@GMAIL.COM