PART 1

My story begins late in the summer of 1975. I was 16½ years old and not feeling quite right. I had worked as a counselor at a day camp in my neighborhood and was preparing to enter Grade 11 at William Lyon MacKenzie Collegiate in North York. But, I just couldn’t shake a malaise that was dogging me.

One evening, for no particular reason, I stepped onto the scale my mother kept on the landing of our stairway to the basement. Whenever I had recently done so, my weight hovered between 145 and 150 pounds. Somehow, I remember the number 149 coming up most frequently. This time, the number read 139. I picked up the scale; looked to see that it was properly adjusted, and then set it down. Stepping on once again, the number 138 came up. It concerned me, but I rationalized that I’d been outdoor and active at camp throughout the summer and may have worked off ten pounds. Then, that unshakable malaise came to mind and I told my mother about the weight loss. As a parent would, she seemed a bit more concerned, but also felt I may have slimmed down by way of physical activity. She told me to keep track of how I was feeling and — if necessary — we would visit the doctor.

As the days and weeks progressed, I realized I was having some difficulty after eating a meal, and my energy was not where it should be for a person my age. The previous autumn — in my first year of high school — I had played football for MacKenzie and thoroughly enjoyed myself (even though the team was horrible). I had looked forward throughout the summer of ’75 to playing once again and was very disturbed to recognize, after only a few workouts, that I simply did not have the stamina to continue. I stepped aside and was called a “quitter” by my coach.

This was kind of hurtful, but it also angered me. Why would a school–teacher jump to such a conclusion? It wasn’t that I had no desire to play. I simply couldn’t. As it turned out, the coach’s insensitivity was the least of my problems. I was having rather severe abdominal discomfort after eating — to the point where I began to fear the next meal. Or, even a mid-day snack. As I increasingly avoided food, my weight continued to drop. A physical issue was morphing into something deeply emotional.

Around mid–October, my parents took me to visit our long-time family doctor. He could see the anxiety when I spoke of my deteriorating condition and weight loss. Given that my mother had been prone to depression, he wondered if I may have been exacerbating a minor condition by worrying about it to such an extent. To be sure, however, he ordered a full set of blood–work and an Upper–G.I. series X-ray (G.I. standing for gastro-intestinal). As you’ll see, this would prove inconsequential and, in fact, quite a blunder on the doctor’s part.

To show you how fortunate I’d been with health issues until that point, the notion of a simple blood–test frightened me. If they took too much blood, would I pass out? Would the technician poke me and miss the vein? Frivolous stuff. As usual, when you worry about something irrationally, it causes undue stress — exactly what I didn’t need at the time. The procedure, as you might imagine (or know from experience), was a piece of cake and I felt silly to have worked myself up over it.

A few weeks later — still suffering after meals — I went to Mount Sinai Hospital here in Toronto for my Upper–G.I. Series X–ray. For this procedure, I drank, through a straw, a thick, white, chalky liquid called Barium. It looked like a vanilla milkshake but did not taste like one… trust me. Barium is a radio-contrast agent that coats the inside of the gastro–intestinal tract and enables the hollow structures of the esophagus, stomach, small intestine and colon (large intestine) to be imaged via X–ray.

A Barium–swallow is effective in diagnosing Crohn’s Disease only if the liquid is permitted to pass through the stomach and into the intestines. This is known as a Barium follow–through and requires several hours of periodic imaging before the contrast solution makes its way through the entire length of small and large bowel. For an Upper–G.I. Series — which I underwent — only the esophagus and stomach are examined. Crohn’s Disease can occur at any juncture along the G.I. tract but is most common in the ileum, or last portion of the small intestine. The length of the small intestine in a male adult is roughly 22 feet and six inches. The ileum occupies the final six feet before the ileocecal valve and juncture to the large bowel.

Given there were no issues with my esophagus and/or stomach, the Upper–G.I. X–ray came back negative. My doctor had erred by not ordering a Barium follow-through, which would have clearly shown the large mass of inflammation in my small intestine and colon. With no clinical evidence of disease — and my growing angst over not feeling well — the doctor concluded I was suffering from emotional duress; that my symptoms were largely psychosomatic. He prescribed a course of Valium to calm the unease and bring resolution to my “imagined” illness.

During this juncture — November and early–December 1975 — high school teachers in North York were on strike. But, I sure as hell wasn’t enjoying the extended vacation. The Valium I took for my “emotional disorder” most certainly relaxed me. I was in a catatonic state for much of the time, which only served to make my increasingly painful bathroom visits more arduous. Somehow, I took comfort in a fast–approaching trip to Miami Beach for the ’75 Christmas break with my family and two closest friends: Jeff Spiegelman and David Silverman. Still clinging to the doctor’s contention of psychosomatic malaise, I hoped the ocean; the beach, and the warm, Florida sunshine would bring me around. Oh, how I hoped it would.

In September 1975, my father had bought a pair of season tickets for the Toronto Maple Leafs. They were in the south mezzanine (or balcony) Blues at Maple Leaf Gardens — behind and to the left of the goal the Leafs defended in the first and third periods. Having been a hockey fan for as long as I could remember, it was quite a privilege to attend all the games. The Leafs were beginning a brief stretch of exciting hockey, led by good, young players Darryl Sittler, Lanny McDonald, Errol Thompson, Dave (Tiger) Williams, Borje Salming and Ian Turnbull. But, my deteriorating health situation began to counter the novelty and enjoyment of going to the Gardens.

The night of Dec. 13, 1975 is still vivid. Leafs hosted the New York Islanders and I remember the excruciating discomfort in my belly as David and I rode the subway to College St. During the five–minute walk from the subway station to the arena, I had to step aside twice to vomit in a construction site next to the Gardens. The pain would not subside and I threw up twice more in the arena before David wisely suggested we leave and head back home. I stayed at his house that night, wondering, beyond reason, how I could have worked myself into such a dilemma.

Then came the Florida trip.

As long as I live, I’ll not forget being sprawled on the livingroom couch — totally strung out on Valium — as we awaited a limo to the airport. I was in a complete fog during the three–hour flight from Toronto to Miami, though I do recall enjoying the taxi–ride across Biscayne Bay to Miami Beach… and the site of the blue/green Atlantic Ocean through the floor–to–ceiling windows of the Seville Hotel at Collins Ave. and 30th St. (long–since demolished for a condominium complex). Jeff, David and I checked into our room; changed, and went down to the hotel pool.

That “vacation” was an absolute nightmare.

It should have been one of the best moments of my youth… but I was so sick.

We were on the “American” plan at the Seville, which meant breakfast and dinner was provided each day. The dinners would include rolls, soup, salad, a main course and desert. I would usually make it past the rolls, but the first or second spoonful of soup would send me scurrying back up to the hotel room to vomit. I’d then re–join my family and friends and watch as they ate the remainder of their meals. David later told me there was more than a little concern at the table after I left. The psychosomatic theory was still out there, but Mom and Dad were no longer buying it.

I remember one night when David and Jeff were out having a good time with other kids in the hotel. I was laying between my parents and crying — my stomach cramped with pain. I couldn’t have weighed more than 120 pounds, 30 less than when I first weighed myself in September, and I looked as sick as I felt.

“What’s happening to me, Mom?” I wailed as she held me in her arms. Dad then interjected, “Don’t worry, How, we’re taking you to a very well–known doctor at Toronto General Hospital when we get home. He’ll look after you… I promise.”

We flew back to Toronto on Jan. 2, 1976. As if I needed something else to worry about, the flight was delayed more than two hours in the Florida sun as Air Canada mechanics re–installed some part on the plane. When we took off, the DC–8 jet banked sharply to the left over Biscayne Bay. We could see the road that took us from Miami Airport to the beach. David and I were squeezing each other’s hands until they were white. “I thought the part failed,” he said after we had leveled off. It felt comforting to land at Toronto International Airport on that late–Friday afternoon.

The following Wednesday, Jan. 7, I was driven down to Toronto General Hospital and admitted for testing under the care of Dr. Khursheed N. Jeejeebhoy — a native of Burma (b. 1935) and one of the foremost experts on treating inflammatory bowel disease. If you’re wondering why I hadn’t yet worried over the possibility of cancer, it’s that I didn’t know anything about it at 16 years of age. And, thank God.

My mother, however, had almost convinced herself I was dying; I weighed all of 115 pounds and looked emaciated when Dr. Jeejeebhoy walked into the four–patient ward at TGH and introduced himself. A short man with black hair, thick glasses and a warm smile, “Jeej”, as we would later call him, put his hands on the lower–right portion of my stomach and felt it in a rolling motion.

Not five seconds later, he said, “You have Crohn’s Disease.”

“I have what?”

“Crohn’s Disease. I’ll be back.”

With that, he went out into the hallway to see my parents. Mom, sick with worry, looked at him and said, “Please, doctor, just tell me he doesn’t have the big C.”

“Well, he does,” answered Dr. Jeejeebhoy, who then smiled and said, “but not what you’re thinking. Your son has Crohn’s Disease — an inflammation of the small and large intestine. That’s why he’s been so sick. We’ll be able to treat him here.”

Mom later told me she was ready to slap and hug the doctor at the same time. She nearly fainted when he said “Well, he does” and then suppressed a brief moment of anger over Dr. Jeejeebhoy’s gallows humor before finally exhaling with relief.

Meantime, I was in the room thinking, “Bones Disease? Loans Disease? What did the doctor just say?”

He came back in with my parents. “We’re going to do some tests in the next few days to see how much (bowel) involvement you have. In the meantime, you just relax and stop worrying. We’ll get you feeling better.” I asked about my ailment. “Crohn’s is a chronic disease; an inflammation of the bowel,” the doctor replied. “We don’t know what causes it and there is no cure.” I suddenly became very frightened, as I figured that a disease with no cure would doom me rather quickly.

“Does that mean I’m going to die?” I asked Dr. Jeejeebhoy.

“No, no, no — don’t be silly,” he laughed. “There are very good controls for this disease with medication and diet. But, we have to see what’s going on. You’ve been fighting this for several months without any help. That’s why you’ve been in so much pain. You’ve been throwing up because of the pain. We’ll get some medicine to help you feel better. You’ll be in here for at least a week.”

“Well, I guess I can forget about going to the Leaf games for awhile.”

“Oh, you like hockey?” asked Dr. Jeejeebhoy.

“Yes, I have season tickets. Leafs are playing Philadelphia tonight.”

“When is the next game?”

“Saturday night.”

“Okay, we’ll give you a pass for a few hours so you can go. Then, you’ll come back afterward. How does that sound?”

It was the first time in weeks I actually felt like smiling.

When the tests were explained to me, I stopped smiling.

The first would be a Barium enema; the second, a small–bowel enema.

The word “enema” is enough to disgust most people but it simply implies the infusion of liquid for an X–ray. The Barium enema would be infused into my rectum to examine the large bowel. The small–bowel enema would require passage of a nasogastric (thin, flexible, plastic) tube through my nose and down into my esophagus and stomach so that Barium could be infused directly into the small intestine. Neither procedure sounded overly pleasant, but the notion of having an instrument up my back–side was particularly unappealing.

A large dose of anti–inflammatory medication delivered through an intravenous (or I–V) line in my arm quickly reduced the pain and swelling in my abdomen. It was nice being able to roll over onto my stomach without searing discomfort. Of particular delight was a nightly back–massage, with lotion, performed by whichever nurse was assigned to my bed. I distinctly remember that one nurse was very attractive while the other resembled an outside–linebacker. When the former did the massage, I was happy to be on my stomach for fear of embarrassment… if you get the drift.

On Saturday night, as promised, I was allowed to leave the hospital for a few hours. Dad picked me up and took me to the Maple Leafs–Los Angeles game at the Gardens, about a mile east, on Carlton St. It was nice to be away from Toronto General but I’d been laying around for three days and felt kind of foggy. The arena, so familiar to me, seemed almost like a foreign place, which took me by surprise. It was actually comforting to return afterward and crawl back into my hospital bed.

I had the two procedures early in the week. To my surprise — and delight — the Barium enema was pretty much a breeze, though it required immense concentration and muscle control. While laying on my left side, a small, bulbous tube was inserted into my rectum and held in place by a tiny, inflatable balloon. Barium then flowed into my colon through the tube. As the Barium collected, the urge to defecate was immediate and somewhat overwhelming — thus the requirement for muscle control. Evacuating the liquid, as I desperately wanted to, would simply have led to another infusion. As such, “holding it in” was mandatory. I rolled onto my back; my right side, and partially on my stomach. The X–ray table was also maneuvered to help coat the entire large bowel. Once or twice, the technician delivered some air into the colon for better contrast, which only heightened the desire to defecate.

I would have beaten any world–class sprinter to the bathroom when the tube was removed.

The small–bowel exam, which I had feared less, was exceptionally difficult, mainly because I tensed up. The technician inserted the nasogastric tube into my nose (which was uncomfortable, but not painful) and down toward my throat. He then told me to sip water through a straw. In later years, I learned to do this properly and the tube advanced through my esophagus into my stomach without issue. On this occasion — being young and very nervous — I did not swallow the water at the precise moment. As such, the tube went into my trachea and triggered my gag–reflex. It happened three or four times and I began to sob uncontrollably. I remember the technician growing impatient, which only increased my anxiety. A female colleague then came into the X–ray room and calmed me down. I still recall how understanding she was. When she took over, I was able to swallow the N–G Tube, and the examination was completed within ten minutes.

I was a bit traumatized by the experience and broke down in my mother’s arms when I returned to my hospital room. Dr. Jeejeebhoy came in and understood my reaction. “But, the worst is over now,” he said. “There will be no more tests.”

Having been on I–V anti–inflammatory medication for nearly a week, my stomach felt absolutely perfect and I began craving food for the first time in nearly three months. Eating a meal — even hospital food — without abdominal pain and cramping was delightful. I remained in hospital until Jan. 17, awaiting the X–ray results and a medication plan to go home with. It’s funny the things that stay with you. All these years later, I can remember listening on radio to a Leafs road game against the old Kansas City Scouts. Looking up the date, it was Jan. 15, 1976 — a Thursday night.

I was sent home on large doses of Prednisone — a synthetic corticosteroid and one of the most powerful anti–inflammatory medications. When you take Prednisone for more than a week, Adrenal supression begins (the Adrenal glands essentially shut down). The weaning process, therefore, is very gradual, which enables the glands to start producing on their own. If I recall correctly, I began with 80 mg of Prednisone — or 16 tablets a day. The pills are round and very small, so swallowing six to eight at a time is quite doable. But, Prednisone does have some grievous side effects when taken in large amounts, or for a long period of time. It is not an easy drug.

Among the noticeable side effects are acne and a severe rounding of the face. I looked like a moon–pie within ten days and wasn’t happy about it. I was also on a drug called Salazopyrin, another anti–inflammatory agent. It threw me for a loop. I remember being in History class at MacKenzie (once the strike ended) and watching my teacher’s head move side–to–side. The fact Mr. Price was standing perfectly still was immaterial. As far as I was concerned, he had some kind of a tremor.

With my cocktail of medication, I had difficulty concentrating on school–work. I wasn’t in abdominal pain, but I felt like I was off on some distant planet. With school not going well, I turned to my favorite subject: Hockey. It was nice to be attending Leaf games once again. One such encounter — the most memorable in my life, to this point — occurred on Feb. 7, 1976 when Darryl Sittler erupted for 10 points (six goals, four assists) against Boston at Maple Leaf Gardens in an 11–4 Leafs romp. That record for most points in a game stands to this day, having survived — among others — Wayne Gretzky and Mario Lemieux. I used up every ounce of precious energy yelling myself silly that night in the arena. The place was nuts.

No one had made any promises about the direction of my new, chronic disease, but I couldn’t shake the notion that another shoe was about to drop. Sadly for me, it wasn’t a shoe, but a large, wooden clog. On Feb. 21 — two weeks after the Sittler eruption — I sat with David in rail seats at the Gardens for a game against Buffalo. Rails were seats in the front row, at the glass, and these were right next to the visitors’ penalty box. Quite a unique perspective. After the game, David and I went to a nearby Fran’s restaurant for a bowl of spaghetti. Nothing seemed out of the ordinary when we took the subway home just after midnight. It would, however, turn out to be my last night spent out of hospital for the next 48 days.

PART 2

Part 2 of my story begins on the morning of Sunday, Feb. 22, 1976. I had been home for five weeks after the diagnosis of Crohn’s Disease at Toronto General Hospital. The side–effects of powerful anti–inflammatory medication had left me comfortable, but in an emotional fog. I wasn’t sure what direction my illness would take, yet I had a constant feel of impending doom — partly as a result of the medication, but also my intellectual awareness that months of clinical malaise would not “go away” forever. As mentioned toward the end of Part 1, there was a perpetual sense of another shoe about to drop. When it finally did, I began a six–week sojourn toward my first abdominal surgery.

I awoke on that Sunday morning with a slight irritation — almost an itch — in the mid-line of my stomach, below the navel. I figured maybe I was hungry, or there was some trapped gas in the area. But, when I pressed on the spot with my fore and middle–fingers, a jolt of pain ran through my abdomen. Within seconds, I began to have cramps, but not like those prior to my diagnosis. These generated more of a knifing discomfort that repeatedly built and subsided. I could not imagine what I’d done by touching the area but, clearly, something was very wrong.

My pal, David Silverman, had stayed over after we’d attended the Toronto–Buffalo NHL game at Maple Leaf Gardens the night before. David told me the other day Mom and Dad had cryptically asked him to leave that morning after the pain started. He said he knew something was up, but had no details of my plight. Neither did my parents. Or me.

Within moments, we put in a call to my Gastroenterologist — Dr. Khursheed N. Jeejeebhoy — at Toronto General Hospital. He phoned back and suggested my Dad run to the pharmacy and pick up an over–the–counter drug called Buscopan. It is an anti–spasm medication that could slow my abdominal cramps. I took the little white pill and waited a few moments. It had no effect. I then laid down. One half–hour later, there was still no relief. At that point, we called Dr. Jeejeebhoy back and he directed us to meet him at the Emergency Department of TGH.

My God, was I in pain.

I remember being doubled over in the back seat of my father’s car as he drove me and Mom downtown. The rest of that day is somewhat a blur though I distinctly recall how disappointed I was when the doctors told me they could not administer pain medication through an intravenous (I–V) line for fear of “masking the cause of your discomfort.” If anyone needed a dose of Demerol or Morphine, it was yours truly and my parents thought it was a somewhat barbarous way to treat a 17–year–old kid. Nonetheless, I had to battle the pain until doctors figured out precisely what was causing it. As would happen today, I went for a simple flat-plate X–ray — laying on my back for a quick image that would determine the air patterns in my bowel and whether or not I had an intestinal obstruction. It came back negative but my temperature began to soar as high as 103 degrees F. That’s when the doctors knew some form of infection was occurring and that by pressing on my stomach earlier in the day, I had likely triggered an intestinal perforation.

Crohn’s typically presents itself as I mentioned in the above paragraph. The small intestine can inflame inward and create a blockage. The peristaltic (wave–like) movement of the small bowel — contractions that begin upon ingesting food and force previously ingested matter toward the colon (or large intestine) — increases in magnitude, trying to “push through” the contents. This causes severe abdominal cramping.

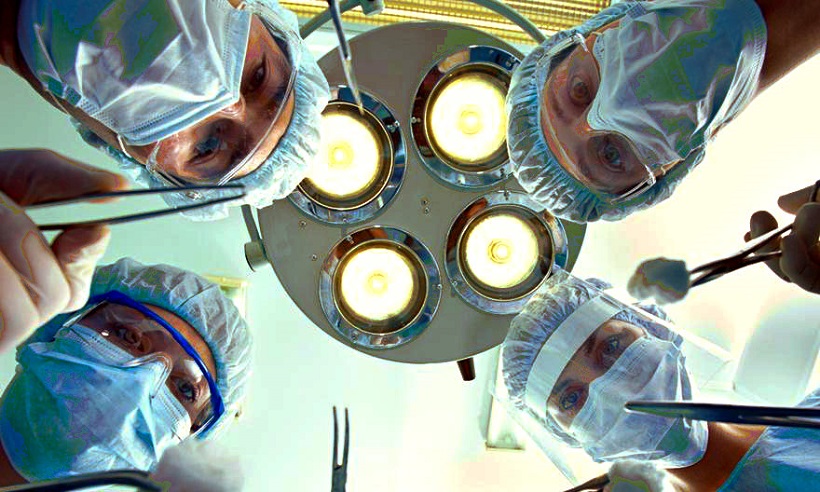

Another predicament is a thinning of the intestinal wall that results in a perforation, or tear. Bowel contents can spill into the abdominal cavity and cause serious infection. This is almost always treated with emergency surgery… unless doctors determine the patient is somewhat stable. Operating in the throes of infection is perilous and risky — undertaken solely if a person’s life is endangered. Doctors much prefer treating infection with intravenous antibiotics, and then performing surgery (if necessary) once the ailment has “settled down.”

In my case, the Emergency staff elected Door No. 2. Large doses of antibiotic medicine flowed into me through an I–V line and I was finally administered some Demerol — a synthetic, toxic opioid that isn’t used anymore because of its convulsive and hallucinogenic potential. Whether or not I hallucinated on Feb. 22, 1976 is immaterial. The narcotic reduced my pain while the antibiotics attacked my bowel infection. I was moved, early that evening, to a private room in the College St. wing of Toronto General, directly across from the nurses’ station — my condition listed as “serious but stable.” Quite the day.

Once settled into the room, all I wanted to do was sleep. I had used up so much physical and emotional energy fighting the intense pain that I had nothing left. I recall a nurse attaching a bag of intravenous Gravol (anti–nausea medicine) to my line. That knocked me out good. I must have slept like a rock because I still remember waking up what seemed like 15 minutes later only to see daylight creeping through the blinds. It was actually past 9 a.m. on Monday — 12 hours after closing my eyes. Remarkably (and delightfully), I was in no pain. None whatsoever. This not only surprised me, but the doctors and nurses who made rounds that morning. What it meant, the doctors weren’t entirely sure, but my temperature had fallen to a manageable 100 degrees F — an indication the antibiotics were working and that no large amount of intestinal matter had seeped through the perforation into my abdominal cavity.

Dr. Jeejeebhoy, always at the forefront of research, was among the pioneers of a treatment known as TPN — Total Parenteral Nutrition. It allows a person to be “fed” intravenously for a long period of time; in my case, long enough for the bowel infection to completely heal before deciding on the next course of action. A typical intravenous line — inserted on top of the hand or the inside of an arm — allows for saline (essentially salt–water) to flow into the body for a finite period. If you have ever required a visit to the Emergency Department of a hospital, chances are the attending nurse has started in I–V, which also allows for medication to be administered. The veins in the hand and arm, however, can only tolerate an I–V needle for several days before they become swollen and painful. And, they can only accommodate normal saline, which keeps the body hydrated but does not contain nutrients.

As such, TPN (also known as hyperalimentation) was introduced in the 1970’s. It requires a vein with a large diameter that can bear an invasive object much longer. At the time of my illness, a needle–like catheter had to be threaded into the subclavian vein, located beneath the clavicle (or collar–bone). It can be the diameter of an adult “pinky”–finger, allowing for more dense liquids such as amino–acids, lipids and other dietary minerals. Weight can be maintained to a large degree via this method. Dr. Jeejeebhoy felt it would take a couple of weeks before further assessment could be done on my bowel. He therefore prescribed TPN.

Two doctors (one of them a surgeon) and a nurse came into my room on Monday afternoon to insert the catheter.

Given the subclavian vein leads directly into the heart, I had to hold my breath and remain perfectly still when it was opened to accommodate the catheter… and during times, later on, when the spot was cleaned. I took several injections of Novocaine to freeze the area beneath my collar–bone and felt only a slight pressure (but no pain) when the catheter was inserted. It was protected by a metal device that had to be held in place by three stitches. The only pain occurred when the third stitch punctured an area of skin not numbed by the Novocaine. I nearly jumped to the ceiling and the doctor apologized profusely. The entire contraption was protected by an adhesive dressing on my upper–chest that required sanitizing and changing twice a week. The catheter was attached to a lengthy intravenous line I carried around on a pole that I named “Delores” for some reason. She and I became very close friends.

As an aside, long–term intravenous nutrition today is commonly administered through a PICC line — short for Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter. It is a long, slender, flexible tube introduced into a peripheral vein, typically on the inside of the upper–arm, that terminates in a larger vein near the chest. I had a PICC line after a complication from my most–recent Crohn’s surgery in December 2006. Again, I was implored not to breathe when the tube neared my heart. But, it was a far–less invasive procedure than in 1976 and the peripheral site (on my arm) allowed for full mobility. I had to be more careful in moving around after the subclavian introduction three decades earlier.

After the TPN line was inserted in ’76, I had to wait in hospital until the doctors figured out what to do next. Each night, a bag of yellow saline (it looked like urine) and a small, upside–down bottle containing Intralipid — a white, milky substance — was hung from my I–V pole and “dripped” into me. This prevented thirst and hunger, as the note outside my hospital door read “NPO” (nothing per oral). After a few days, I became somewhat envious of other patients when I saw dinner trays being delivered to their rooms. Imagine being envious of hospital food.

As with my first stay at Toronto General back in January, much of my time was spent reading books and following the Toronto Maple Leafs.

In fact, the Leafs provided me quite an emotional boost in the first half-week of my TPN/NPO “visit.” Again, it’s remarkable what stays with you through the decades but I’ll always remember laying in my darkened room with the door closed on that first Monday night and listening to Foster Hewitt call the Atlanta/Toronto game at Maple Leaf Gardens. Leafs routed the Flames, 7–1, and it turned out to be the final broadcast of Hewitt’s pioneering career. He had invented hockey on radio in 1923 and became a household name from coast–to–coast in the days before television. Stories abound of Canadians huddling around their radios on Saturday nights in the 1930’s, 40’s and 50’s as Hewitt described action from his gondola perch at the Gardens. Foster died in April 1985. His son, Bill Hewitt, called Maple Leaf games on TV throughout the 60’s and much of the 70’s. He passed away in December 1996.

Two nights later (Feb. 25), I watched on TV as the Leafs obliterated Detroit, 8-0, at the Gardens — establishing team records that still exist for shots on goal in as game (61) and a period (25, in the first). With all the I–V lines sticking out of me, I was pleased that “my team” had outscored the opposition, 15-1, during my first three nights at TGH.

But, the following Sunday — Feb. 29, 1976 — turned into a nightmare.

Late in the afternoon, and quite suddenly, I began to feel intense pain in my abdomen. I was dizzy and very nauseous. The nurses ran in and took my temperature, which had again soared past 102 degrees F. This was quite a surprise given that nothing had gone into my digestive tract for more than a week. I staggered into the bathroom several times to throw up and remember thinking “this is what death must feel like” — not exactly the notion a 17–year–old wishes to have. Dr. Jeejeebhoy didn’t work on Sundays but was called in very quickly. Even he looked alarmed when he saw me. I hugged my father and told him how much I loved him. The way I felt, I really did not think I was going to last much longer.

Another distinct memory is Dr. Jeejeebhoy summoning medical personnel into the hallway outside my room. This was hardly comforting but I was in so much agony, it didn’t matter. He came back in and said the intestinal perforation was probably spilling bowel contents into my abdominal cavity once again. The nurses quickly added antibiotic medicine to my I–V pole as I prayed for the discomfort to subside.

And then — almost as suddenly as it started — the stomach pain and dizziness went away. Within minutes, I was feeling “normal” again… whatever “normal” was during my illness. To that point in life, I had never felt such relief over anything. It had been a six–hour bout of pain, nausea and emotional upheaval that no one should have to endure.

Dr. Jeejeebhoy came back for a third time just prior to midnight and was very pleased to see the turnabout in my condition. Quite chillingly, he said that fellow doctors had been imploring him to rush me into the operating room for emergency surgery. His experience kicked in, however, and felt that it may not be necessary. Again, unless one’s life is imperiled — and it was close with me — doctors blatantly prefer not to operate in the throes of infection. Given that I’m writing this story more than 41 years later, Dr. Jeejeebhoy made the right call under duress.

Three nights after that came another unexpected surprise.

I was listening on radio to a Leafs game in St. Louis when the head nurse knocked and said she was moving me to another room. On one hand, I felt this was good news; I had been directly across from the nurses’ station so they could keep a close eye on me — sort of a one-bed Intensive Care Unit. Conversely, I’d gotten used to my surroundings and didn’t really want to leave. A slight protest went nowhere — the nurse confirming she needed my bed for a sicker patient. When she led me to my new room, however, I quickly became distraught.

It was a six–person ward — the other five beds with men that could have been my great–grandfather. Or so it seemed. If not for the fact they were snoring obnoxiously, I would have mistaken them for corpses.

What a night that was.

After phoning Mom and Dad in somewhat of a panic, I drew the curtain around my bed and reluctantly crawled in. The “Rip van Winkles” were sawing wood like you’ll never hear. It was loud and guttural, like a death rattle. I had no idea how I’d be able to rest for even a minute. I reached over to the end–table and grabbed a sheet of Kleenex. I then tore off two large pieces; balled them up, and stuck one in each ear. That took the edge off the ruckus and I somehow drifted into semi–sleep.

Three times during the night, however, I was startled by commotion — bells, horns and “Code” announcements. On each occasion, someone rushed into the room (my bed was next to the door) and then walked out in much less of a hurry. I had an idea what was happening and no desire at all to peek through the curtain. In the middle of the night, things settled down… and the snoring didn’t appear to be as loud.

I think you know where I’m going here.

Upon waking up after 7 a.m. and walking through the curtain, three of the five beds were vacant. Yes, all three had been casualties during the night. The person rushing into the room next to my bed was either a doctor or a priest. The person casually strolling out was an orderly on his way to the “refrigerator.” Though I’m making light of it now, it was traumatic at the time. I ran over to the nurses’ station and said, “Why do I have to be in a room with dying men? Isn’t there another place on this floor you can put me?” I would have settled for the broom closet. My mother took up the argument when she arrived later in the day.

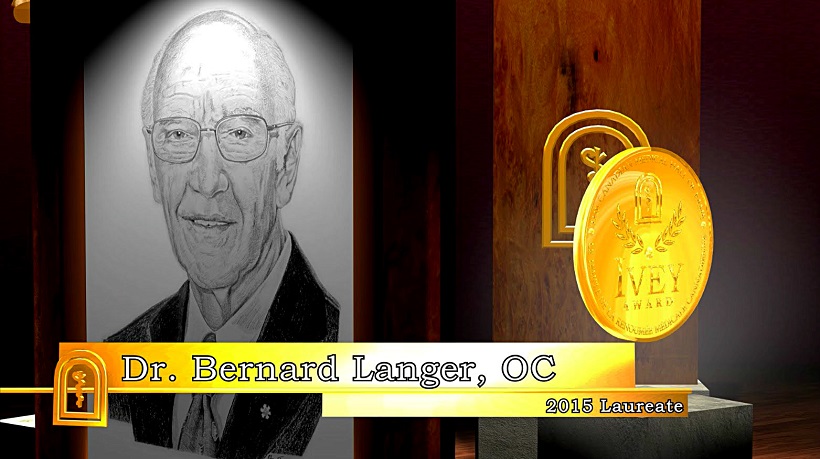

Meantime, I got some other news — hardly unexpected, but discouraging nonetheless. I was visited by Dr. Bernard Langer, the hospital’s chief general surgeon. Tall and gangly — in his late-40’s at the time — he gave the appearance of a much older man. He was, however, considered (and still is) among the top clinical surgeons in Canada. Matter-of-factly, Dr. Langer said that once my abdominal infection had fully healed, he would operate and remove the diseased portions of my bowel. “I’ll take out the bad parts and join the good parts together. This is something I do on people from infants to senior citizens. Don’t be worrying about it.”

Oh sure. Don’t worry about my stomach being cut open.

Though I suspected I wouldn’t leave Toronto General without having surgery, the confirmation hit hard. I cried in my mother’s arms several times that day as she tried to comfort me. Lost in my own despair was how it affected her (and my father) — something I wouldn’t fully understand until becoming a parent, myself, nearly 21 years later.

Later that night, after visiting hours, I found some much–needed resolve.

And it completely eliminated my fear over having surgery.

Still in the six–patient ward, I walked into the bathroom; sat down on the toilet–lid and gave myself one hell of a pep talk: “Howard,” I said in a whisper, “you will be asleep during the surgery. Dr. Langer will remove all of your diseased bowel, enabling you to resume life as it used to be. Afterward — though in some discomfort — you’ll receive injections of narcotic medication that will not only relieve the pain, but (according to a nurse I spoke with that day) make you feel as if you are ‘floating.’ And, most of all, it will allow you, finally, to leave this hospital.”

That’s all it took. Seriously.

And, it taught me an important lesson: No matter how much we may lean on others in a time of apprehension and fear, we must summon internal fortitude. We all have it. Drawing it out, though, is undeniably a challenge — harder for some than others, but a chore nonetheless. By the grace of God, I was able to resolve my fear during those few solitary moments. It ended the disquieting unease of two long weeks spent wondering if and when I’d be able to “live” again. I can vividly recall the number of times I would walk with my I–V pole to a window overlooking College St. and gaze enviously at those on the outside — strolling along the sidewalk; entering or leaving the street–car that stopped directly across the road. Mindless matter, to be sure, for those not confined to a hospital, but Utopian for a bewildered 17–year–old.

With my new-found courage came another pleasant surprise. Early on the morning of Mar. 5 — after two “enlightening” days in the dead–man’s ward — I was moved to a small, private room on the opposite side of the floor. There, I would remain for 3½ weeks until my surgery.

PART 3

Part 3 of my story begins at Toronto General Hospital on Saturday, March 6, 1976.

Wonderful news arrived early in the morning when a nurse stopped by to say I’d be moving out of the six–person ward into a private room on the opposite side of the College St. wing. As gruesomely detailed in Part 2, I was in the ward when three of five elderly men croaked in the middle of the night, Mar. 4. The following day, it was confirmed to me — in the same room — I would definitely require surgery to remove the portions of intestine affected by Crohn’s Disease. Needless to say, it was hardly sweet sorrow when I got the hell out of that miserable place.

The private room was smaller than the one I occupied across from the nurses’ station in my first 10 days at the hospital. It had a window with Venetian blinds that were opened and closed by turning a knob next to the frame. There was just enough territory on either side of the bed for a person to sit. The bathroom was no more than a meter beyond the foot of my bed… cramped quarters, indeed. Still, it felt like the Ritz-Carlton after three horrendous nights in that ward. Given how sick I was when I arrived at the hospital on Feb. 22 — and then again when my temperature soared during the late-afternoon of Feb. 29 — I hadn’t really met anyone on the floor. That segment of the old College St. wing was dedicated to ailments of the gastrointestinal tract, including Crohn’s, colitis and — sadly — cancer.

The day after I was transferred to the private room, I walked out with my intravenous (I–V) pole and did my morning “laps” around the floor. Being tethered to the pole with my TPN (Total Perenteral Nutrition) line, I didn’t have a lot of mobility or many exercise options. Walking around the hospital wing kept my blood moving. On one of my laps, I came upon a young girl — similarly tethered — who flashed me a warm smile. I gathered she was around my age (17 at the time), but she looked emaciated… so thin, that I figured she had been suffering for a long time. I forget her name all these years later but we started talking and she told me she also had Crohn’s and was awaiting an operation. Though I found her to be very pleasant, her story frightened me. This poor, young girl hadn’t eaten for more than two months after a dreadful flare–up around Christmas. She felt she would lose her entire colon (large intestine) and more than three feet of small bowel in surgery. Apparently, the doctors had told her there was no guarantee she would enjoy a post–surgical remission for any length of time. These were not encouraging words.

Nearly four decades later, I understand why her medical team offered such a gloomy scenario. Though she may have been a tad melodramatic — and who could blame her after such a long bout of illness — Crohn’s can theoretically recur while a patient is on the operating table. Were that even sporadically the case, however, doctors wouldn’t waste time opening up people with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Almost always, IBD patients (those with Crohn’s and/or colitis) enjoy long intervals of health after undergoing surgery. I can tell you that, first–hand. Also, excision of the entire large bowel is not uncommon in people with advanced colitis (inflammation confined to the colon) — the disease curable by such means.

In a total colectomy, as it is called, the terminal ileum (last portion of the small intestine) is sewn to the rectum. Patients undergoing this procedure may need an ileostomy (or external “bag”) for some duration. Once fully healed, however, a person can resume most normal activities. Given that water absorption is a prime function of the colon, such individuals can expect upward to six loose bowel movements a day, though drugs can slow the urge to defecate. It is quite rare for Crohn’s to involve the entire colon — to the extent it has to be removed.

Of course, I didn’t know any of this when I spoke to my young friend in the hospital — and neither, I assume, did she. I was a bit shaken when I walked back into my room, fretting over worst–case scenarios (a habit to which I think I’m predisposed). But, she and I continued to talk every day, trying to encourage one another.

Once it was determined I would need a operation, my surgeon, Dr. Langer, made daily visits, checking on the mass of intestinal inflammation he said he could feel while pressing and rolling with his fingers on the lower–right quadrant of my stomach. He also took to performing a digital rectal exam every day — quite the thrill. Initially, when I knew Dr. Langer was making rounds on the floor, I would dive into bed and pretend to be in a deep slumber. Having seen that act a million times, he simply amplified his instruction — “Roll over on your left side, Mr. Berger” — a few octaves and I had no choice but to “wake up.” Somehow, I learned to relax during those invasive moments, which all but eliminated the cramping discomfort. It was also helpful that my surgeon did not have a short, stubby index–finger.

Additionally, I had never been aware of the term “bed–side manner” until I entered hospital. Dr. Langer inadvertently brought it to my attention for his thorough lack thereof. When you are 17 and about to be hacked open, there are questions that need answers. A modicum of empathy is also appreciated — something Dr. Langer refused to impart until minutes before I was rolled into the operating room, when he winked at me above his surgeon’s mask and pinched my big toe. This is not to chastise the good doctor, even though there were days I felt like giving him a digital rectal exam. It’s just that I had no idea a person could be mundane about such a Bunyanesque event as performing surgery. I would eventually understand, of course, that working on innards was as breathtaking to Dr. Langer as changing his socks. But, that did not ease my plight at the time.

Some doctors are more accommodating than others. Dr. Langer was all business and not borne of what he would consider idle chatter. I can still close my eyes and see him looking at me, half–crocked, as I asked something or other. He would offer a curt reply and walk out, leaving me to wonder if I had spoken to him inanely. The nurses and medical residents would shrug and say “That’s just the way Dr. Langer is” — reminding me, instead, of his clinical pre-eminence. After awhile, I begged off discussion, even when he opened the door by asking “Any questions?” I figured if there was an issue, ol’ Bernard would tackle it appropriately on the operating table.

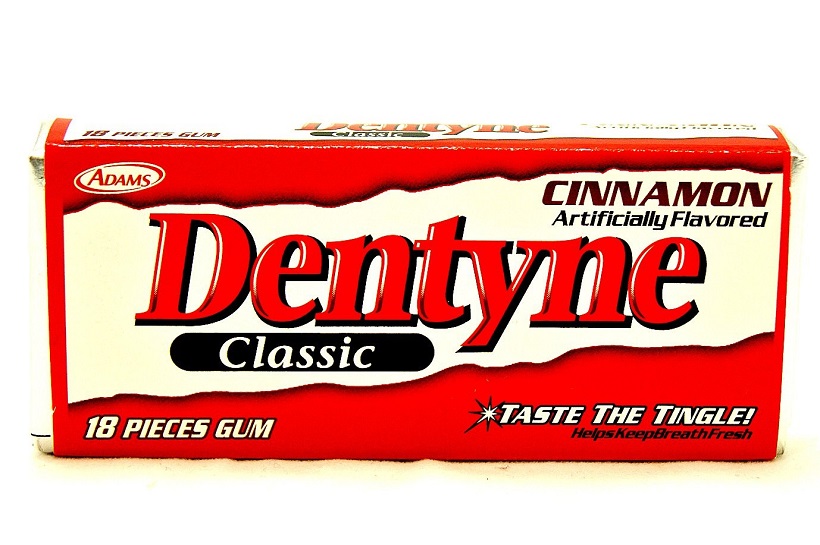

As the days passed, I started to grow a bit frustrated. I was feeling just fine — craving the hell out of food — and no one could tell me when my operation would be. “We have to wait until everything has settled down completely,” said Dr. Langer when I finally asked. I told him I was going crazy looking at and smelling food in the hospital — to the point where I was watching Graham Kerr’s old TV show The Galloping Gourmet each night. Graham’s recipes had my mouth watering. “Well, if you want,” Dr. Langer said, “you can chew sugarless gum. Get a pack of Dentyne. But, nothing else.”

Chew? Actually taste something other than the medicinal odor of my nightly vitamin–saline intravenous? This was almost too good to be true. So much, in fact, that I asked Dr. Langer to repeat himself, just in case I had misunderstood.

“You heard me,” he said, walking out the door.

Gnawing on a piece of sugarless gum is not likely to incite passion. For me, however, it was akin to being offered a steak dinner. Mom ran down to the hospital gift–shop and cleaned out the gum shelf. I nearly crammed the delectable items into my mouth before removing the wrapping–paper. My God, it was heaven to actually experience the flavor of something.

“I see you’re enjoying that,” said my nurse.

I spent time reading voraciously; chewing away, and keeping tabs on the Maple Leafs. I had a radio in my room and I still remember struggling to stay awake during a 7–7 tie between the Leafs and California Golden Seals (Mar. 7, 1976). The game in Oakland started at 11 p.m. EST and didn’t end — with all the scoring — ’til after 2 a.m.

A few days later, I received a surprise–visit from an athlete I greatly admired. Mike Eben was a terrific pass–catcher for the Toronto Argonauts in the 1970’s. Given how the Argos tortured me with their inherent ability to turn victory into defeat, this was a quasi–I.O.U. If Crohn’s — as some theories maintain — is brought on by stress, the Argos gave me the disease. Just four months earlier, the team had a “can’t-miss” opportunity to make the playoffs in the final game of the 1975 season. All the Argos had to do, at Hamilton, was avoid losing to the Tiger–Cats by 16 points. They were beaten, 26–10. My abdominal pain began shortly thereafter.

I told Mike the story. “You could be right,” he laughed. “My stomach didn’t feel particularly well after that game either.” I don’t recall how Mike knew I was in the hospital, but I remember enjoying his company; talking football with him for nearly an hour, and being very appreciative of his kind gesture.

My growing impatience with laying around the hospital ended suddenly one afternoon in the middle of March when I began to feel nauseated and dizzy. “Oh no… this can’t be happening,” I said to myself, though I did not have any stomach pain. During my two previous bouts of nausea, vomiting and light–headedness — Feb. 22, when I was admitted to hospital and Feb. 29, when my temperature soared past 102 degrees F — there was severe abdominal cramping. Fearing my intestinal–wall perforation might again be leaking bowel contents, the nurses put in a call to Dr. Langer. One of his interns came up to see me and he wasn’t particularly alarmed after I told him I had no stomach pain. “If the perforation has opened, you’d be in agony right now and running a high fever.” He then asked a nurse to change my bottle of intravenous lipid, thinking it may have somehow been contaminated. The nausea and dizziness subsided a few hours later.

I was told the next morning that my surgery would be performed on Mar. 29 — a Monday. Though I’d long-since talked myself out of dreading the operation (as detailed in Part 2), a bit of fear suddenly recurred. “That’s perfectly normal,” said one of my nurses later in the afternoon. “You’ll feel better tomorrow.” She was bang–on. After sleeping on it for a night, my courage and confidence returned. Both were enhanced by the wonderful image of leaving hospital and getting back into the swing of life. Finally, I knew when Dr. Langer was going to “fix” me.

Thankfully, the days leading up to my operation did not drag. A young fellow that had recently undergone Crohn’s surgery came to visit and said the entire process was a breeze. “It’s all about attitude,” he insisted, “and you seem to be in the right frame of mind. Don’t look back. Keep looking forward. You’ll find the surgery is much less difficult than the events leading up to it.” That, I could believe, given all I had been through since November — four long months of pain, fear and confusion. Getting on with the “show” was my focus heading toward Mar. 29.

Well, maybe not my entire focus.

You see, hormones tend to flourish in young men. At 17 — and hospitalized indefinitely — the 80–year–old Korean woman mopping the floor outside my room began to look good. That’s when Melanie (name slightly changed) arrived on the scene. She was a young, attractive nurse that had been transferred to the G.I. ward. With dark eyes; layered, shoulder–length hair and splendid enhancement beneath the shoulders, I was startled when she walked in one evening.

“Hi, Howard, I’m Melanie and I’ll be your nurse tonight,” she said with a doting smile. The fact she called me “Howard” and not “Mr. Berger” was enchanting.

As she took my temperature and blood–pressure, I briefly considered calling Dr. Langer’s office for a postponement. Then I recalled what I looked like: Adorned in a hospital gown; pale; thin; hair disheveled and tethered to an I–V pole. There had to be better options for Melanie. But, when she later admitted to “lingering a bit longer” in my room, I was ready to propose. Good gracious, was she adorable.

The best part of Melanie being on the ward — well, there were two best parts — but the “graveyard” shift allowed time for her to linger in the middle of the night. She wouldn’t purposely rouse me, nor would she have to, as I’ve always been a light sleeper. Merely coming into the room to take my “vitals” would create enough stir and it was never a challenge for me to stay awake. We talked about her life; my life; hospital life; the after–life… and before we knew it, 30 minutes had flown by.

“Don’t you have to take someone’s else’s blood–pressure?” I’d ask.

“Ah, there’s plenty of time,” Melanie would say. “The young patients can wait a few minutes and the older ones may not have blood–pressure anymore.” Then, we’d quietly giggle.

The other “best part” of Melanie reflects to something I wrote in Part 1. Nurses in the G.I. ward at Toronto General performed a nightly back massage on their patients. Actually, “massage” is kind of an embellishment. It was more of a back “rub” — lotion applied until it semi–absorbed, then a top–layer of baby powder. Much preferable, indeed, to a rectal exam but, still, not a massage. Enter Melanie.

Though she offered right away, I was hesitant — from either inhibition or the visceral urge to give her a rub–down. Whatever the case, I would always find a way to avoid the matter (sitting for 20 or 30 minutes in a locked bathroom was quite effective). One night, though, she finally said, “I’ll be back soon to give you a massage. Don’t make me have to tie you down.” The blood drained from my face but she returned — sans rope — a few minutes later. And this, ladies and gentleman, was a massage.

For what seemed like half–an–hour, Melanie kneaded every muscle in my neck, shoulders, arms and back. I was all but paralyzed when she finished.

“So… did you enjoy that, Howie?” she asked (my name now having evolved from “Mr. Berger”… to “Howard”… to “Howee”).

“Count backward from 24 and that’s how many hours are left until the next one.”

“Melanie,” I croaked out, “this may sound silly, but do you give that kind of a massage to all of your patients?”

“Now, that’s just dumb, Howie,” she replied, walking out the door.

Another person I remember from the College St. wing was an orderly named Romeo. He was a native of the Philippines that had moved to Canada a few years earlier. Though his primary task was ushering patients to and from other parts of the hospital, Romeo would stop by my room a couple of times a day to chat. I was always amazed at how much he knew about North American sports, given his brief time here. He could talk about all the teams and players in the NHL, which made for good conversation. But, one night, I was watching a basketball game on TV between the Buffalo Braves and Detroit Pistons from Cobo Hall in Detroit. I knew most of the Buffalo players for their proximity to Toronto and the half–dozen games each year the club played at Maple Leaf Gardens. I couldn’t name more than one Detroit player. Romeo — less than half–a–decade removed from the Philippines — looked at me and rhymed off every Piston by jersey number. It was mind–boggling.

Another crystal–clear memory is the day before my operation — Sunday, Mar. 28. A dozen friends and relatives came to visit and keep me calm. The G.I. floor had a television lounge in which patients could relax. On this day, the Berger contingent hijacked the lounge for a couple of hours in the afternoon. My cousin from Orillia, Ont., Susan Gold (who recently died of cancer), was seeing a British fellow named Wayne at the time. He was an accomplished guitarist that had gotten to know Kenny Jones — then the drummer for Rod Stewart’s band, The Faces. The previous October, Wayne had taken me with him to Maple Leaf Gardens for a Faces concert. We had back–stage passes and I’ll never forget being in the dressing lounge with Rod Stewart and his band members. The Rod Stewart of Maggie May; You Wear It Well and other hits of the early–70’s. That was quite an experience and I remember how pleasant he was when I approached him to say hello.

With 24 hours to go before my surgery, Wayne busted out his guitar and entertained all of us in the TV lounge. Other people from the hospital — doctors, nurses, orderlies, patients — dropped by until the room overflowed. For me, it was a memorable and relaxing way to spend my final day in the College St. wing.

While the gang was still there, one of the nurses came in and ushered me to my room, where Romeo was waiting with an evil smile and a pan of soapy water. “On your back, sir,” he ordered. I rolled my eyes and disrobed, whereupon Romeo eliminated every follicle of hair from beneath my chest to just above my knees. I mean EVERY follicle, including those on some delicate areas. Today, they don’t even bother shaving before abdominal surgery. An operating room attendant clears a narrow “path” near the incision site once the patient has been anesthetized. In 1976, it was the equivalent of a hazing episode. When I tenderly sauntered back into the TV lounge with a queer smile, everyone knew what had just transpired.

Once everybody left that evening and I was on my own, the reality of the situation hit hard. Though I’d been very calm and pragmatic about my surgery, the night before was rather nerve–wracking. Just as I was about hit the sack, I got a call from one of my favorite relatives, Uncle Harold, who stood among the great kibitzers in our family. This time, however, he was dead serious.

“Howie, I hear you’re all nervous and upset.”

“Well, yeah, Uncle Harold, the operation is tomorrow.”

“Ahhh, operation shmoperation. What’s the matter with you? You’ve been stuck in that hell hole for six weeks and you’re going to finally get out into the world again. You’ll be asleep during the surgery and they’ll keep filling you full of really good ‘stuff’ afterward to take away the pain. C’mon, smarten up. Where’s the brave nephew I’ve come to know?”

It was a terrific pep–talk — exactly what I needed at that moment. Uncle Harold had truly calmed me down and restored my confidence.

“Besides, if something happens, they’ll pull a white sheet over you and you won’t know anything about it.”

Like I said… good ol’ Uncle Harold.

Laying in my darkened room and listening to the radio, the song Dream Weaver, by Gary Wright, came on. It was atop the charts at the time and — if you recall — kind of a haunting melody, consistent with a dream. I remember thinking how it perfectly dovetailed with being unconscious during surgery. I drifted off to sleep with the lyrics echoing in my mind.

PART 4

Part 4 of my story begins at Toronto General Hospital on the morning of Monday, March 29, 1976.

I was scheduled at 1 p.m. for my long–awaited Crohn’s surgery at the hands of Dr. Bernard Langer, having been in the hospital for 36 nights. Surprisingly, I was not the least–bit nervous, probably because of that interminable duration and the wonderful image of getting out in the world again. I’d had more than enough time to mentally prepare for the operation and its aftermath.

Upon posting Part 3 of this series, I was asked in a couple of emails how the lengthy hospital term affected my Grade 11 schooling at MacKenzie. It was a very good question and a topic I should have addressed before now. Simply put — and with one vehement exception — my teachers told me to forget about school and get better. They couldn’t have been nicer or more accommodating. One of them sent me a note that I remember to this day, referring to a two–month-long teachers’ strike that ended just after the new year in 1976.

“Considering we were away from school for that long, this is certainly not a year we’d make difficult on you. Just heal up and don’t worry about anything else.” It took a gigantic load off of me.

The lone exception was a phys–ed teacher named Bob Corran, who obviously had good administrative skill, for he later became athletic director at Cornell University in Ithica, N.Y.; the University of Calgary and, more recently, the University of Vermont. While at MacKenzie, however, and as it pertained to me, Corran had no spelling acumen and a complete lack of sensitivity. As I wrote in Part 1, my energy while trying out for the MacKenzie football team in September 1975 was astonishingly poor for a 16–year–old. At the time, of course, I didn’t know the onset of Crohn’s was sapping that energy; I simply recognized that I couldn’t continue. Corran, in all his wisdom, called me a “quitter” and posted a message to that effect on the school bulletin board (along with the names of several others that had second thoughts about playing).

Later, when I was in hospital, and while all other teachers were encouraging me to recover from my illness, Corran sent a note to Toronto General that read: “Shud drop course.” The “o” and the “l” in “shud” were missing, but not the message. To me, the guy was a first–class prick. I later ran into Corran during his university career and we spoke amicably. But, I’ll never forget his appalling lack of compassion during my initial battle with Crohn’s.

I received a couple of surprises on the morning of my operation. First, I was told I could take a shower. For five weeks, that had apparently not been an option, as an intravenous feeding–line threaded into a large vein under my collarbone could not get wet. I would carefully take a bath every other day — avoiding the I–V catheter, which was covered by an adhesive dressing — while ensuring that other “parts” of me stayed clean. Suddenly, on the day of my operation, a nurse taped a large plastic covering over my right shoulder and said I could shower… which I did, rather enthusiastically.

The second surprise was more of a jolt.

When I came back, an orderly was standing beside a hammock–like gurney that could be lowered onto an operating table. Given the time, around 8:30 a.m., I found that confusing. Surely, it wouldn’t take 4½ hours to wheel me downstairs for my 1 o’clock surgery. The nurse came in with a smile. “Dr. Langer had a cancellation and he can take you now,” she said.

“Well, I’m not ready to go,” I replied, somewhat rudely. “I’m not leaving until my parents are here and I couldn’t get a hold of them before my shower. They think my operation is after lunch… as did I.”

“Could you try and contact them again?”

“Well, okay, I’ll see what I can do.”

To be honest, I was stalling. Though it’s true I wanted Mom and Dad to be with me on the way to the O.R., I also had to recover a bit from the unanticipated schedule change. I was hoping to rest in bed for a few hours before the operation. I did not expect the gurney to be there when I got back from showering. But, minutes later, as if sent by God, my parents walked into the room. They had no clue about the early switch and just wanted to be with me throughout the morning.

I still remember the way Mom rubbed my forehead and said, “How, I know this is kind of sudden but it’s also nice you don’t have to lay around here and wait.” Just then — and it’s another moment I’ll never forget — my great–grandmother, Sarah Tobe, walked into the room. She was my Mom’s grandmother and one of her nine children — my great–uncle, Dave Tobe — was also in Toronto General with a heart ailment. Alongside three of the most important people in my life, I was wheeled through a phalanx of hospital corridors to an elevator — at which point, Mom, Dad and Grandma Sarah had to bid adieu. “It’ll seem like 15 minutes and we’ll be together again,” Mom said, inferring how time would quickly pass for me, unconscious, on the operating table. It wasn’t an easy parting.

Despite all of my mental preparation, I was un–nerved when the elevator–door opened into a hallway of operating “theaters.” The orderly deposited me in what looked like a parking spot, with vertical lines equally spaced on the floor — each wide enough to accommodate a gurney. I remember an old, shriveled–up lady in the “spot” to my right and briefly wondering if the operating–room hallway and morgue were in the same place. A few minutes later, a woman wearing a surgeon’s mask came over and stuck a needle into a rubber port on my I–V line. “This will help you relax,” she said, injecting half–a–syringe of fluid.

Within 15 seconds, I felt better than at any time in my life.

She had given me what was known as a “pre–op” – intravenous Demerol, a synthetic opioid I would become more familiar with in the days after my surgery. With no pain yet to control, the narcotic went right to my head and sent me floating on the most euphoric, heavenly cloud imaginable. The doctors could have said that my family had just been murdered in our home and I would have burst into laughter. Dr. Langer came by and winked at me above his surgeon’s mask. “We’ll be underway in a few moments,” he offered while pinching my big toe.

By the time they wheeled me into the operating room, the Demerol buzz had partially subsided. I remember it being a small, square room with a window reflecting natural light beyond the foot of my gurney. It was rather chilly, which I found surprising. I’ve since come to know (and further experience) that operating theaters are maintained at a lower temperature for the comfort of the surgical team. Wearing gowns, masks and gloves, while working under the hot glare of an O.R. light, would be most uncomfortable at normal room temperature.

My “hammock” was lowered onto the operating table, which barely contained the width of my body. Had I sneezed, I would have tumbled onto the floor. Little stands were maneuvered into position on either side of the table for my arms and a sudden buzz of activity ensued, as nurses and doctors hooked up various indicators — a probe on my chest for heart–beat; a sensor attached to my finger–tip for pulse reading and a blood–pressure cuff on my left arm. I then felt a presence over my right shoulder. It was the anesthetist I had briefly met with in my hospital room the previous day. He was now poring a cloudy, yellowish substance into a test–tube–like opening atop my I–V pole.

“We’re putting you to sleep, Howard. You might have a strange taste your mouth and you’ll get very drowsy.”

The doctor was infusing me with Sodium Pentothal — a short–acting Barbiturate for general anesthesia. When put into an I–V line, it reaches the brain very quickly and generates a brief loss of consciousness. Other gasses and medications are then introduced to effect analgesia (loss of response to pain); amnesia (loss of memory); motor–reflex immobility of the autonomic nervous system and drugs to induce skeletal–muscle relaxation. All I remember is a garlicky taste in the back of my throat and the quick, undeniable sense of fainting.

I’ve been asked through the years by people about to undergo surgery if there is a perceptible passage of time while under general anesthesia. “Perceptible” might be a stretch but there is no sense of being put under and then awakening almost immediately. Without question, a three–hour procedure doesn’t “seem” like three hours — or even three minutes. When you become aware of your environment in the recovery room, however, there is recognition that time has passed. Exactly how much, I’ve never been able to determine. Patients actually regain consciousness on the operating table before being transferred to the recovery room, but have no–such memory after a lengthy procedure.

This is much different from amnesic medication introduced prior to an out–patient procedure such as endoscopy or colonoscopy. I remember the weeks of fear before undergoing a scope of my esophagus and stomach in December 1984 — wondering how I could possibly swallow an instrument being advanced into my G.I. tract. When communicating such concern to my Gastroenterologist at the time — Dr. Fred Saibil of Sunnybrook Health and Sciences Centre here in Toronto — I was told, “Don’t worry, Howard, I will send you to Mars.”

To help with apprehension, a nurse injected Demerol inter–muscularly with a needle in the side of my rump. That sent me into narcotic bliss a few moments later but did not eliminate the anxiety of Dr. Saibil entering the room and parking himself to my immediate left. An intravenous “lock” had been inserted into a vein atop my right hand and Dr. Saibil injected a substance through that port. This was liquid Valium. When combined with the effects of Demerol, it was supposed to provide instant amnesia (or loss of memory). Still, I was aware of Dr. Saibil asking me to roll onto my left side… and of him beginning to advance the endoscope toward my open mouth. “Shit, when is this medicine going to take effect?!” I remember thinking in a final moment of panic.

The next thing I knew I was in a different position; in a different room, with different lighting.

There was a nurse next to me. “When is my procedure going to start?” I asked her.

“It’s all over, Mr. Berger. You’re in the recovery room.”

“What do you mean ‘it’s all over?’ I thought I had to swallow the scope?”

“You did… very nicely.”

“You mean I was awake during the procedure.”

“Absolutely. Fully awake and following all instructions.”

“Wow,” I thought to myself, “Dr. Saibil did send me to Mars with that stuff he injected — and just in the nick of time.”

General anesthesia is altogether different.

When your abdomen (skin, layers of muscle) has been sliced and stretched open for three hours, your first recognition in the recovery room is not the passage of time. It is pain. Not uncontrollable pain, as nurses will have administered narcotics prior to you becoming aware of your environment. But, you clearly will not feel as comfortable as when you laid down on the operating table. I remember asking where I was and if the operation had ended — in hindsight, rather dumb given the piercing ache atop my belly. Once I acknowledged awareness, a recovery room nurse came over to administer more medication. That comforted me and I’ll never forget trying to focus on a clock mounted beneath the ceiling across the room. No matter how many times I blinked and shook my head, the hands and numerals on the clock remained fuzzy. Many of us experience such a moment upon awakening from sleep, but the blurriness subsides after a blink or two. There is no such luck upon rousing from the depths of anesthesia.

I then started getting the hiccups, which are annoying under normal circumstances, but excruciating in the hours after having your abdomen opened and closed. Every spasm of my diaphragm caused a jolt of searing pain. This was simply another side–effect of a general anesthetic — though mercifully brief and intermittent. Also common after a lengthy, invasive operation is nausea, though it doesn’t always occur. Feeling nauseous, again, is quite horrible in the best of circumstances. The threat of barfing with a freshly–stitched abdominal wound is more than enough to yell for a bag of intravenous Gravol, which I’ve done on a few occasions. Thankfully, I’ve never gotten to the point of actually having to retch.

I was also drifting in and out of awareness, which always happens in the recovery room phase of surgery (the latter is more desirable). As such, things occurred with inexplicable gaps. One minute, my parents were standing over me. The next minute — or so it seemed — I was being wheeled toward an elevator. Then I was suddenly in a hospital-room bed, without any concept of having gotten there. Injections of Demerol in my upper-leg muscles occurred every four hours but occasionally seemed to happen minutes apart. I’d be looking at Mom sitting next to my bed; blink my eyes, and she’d be gone. In the span of mere seconds, the daylight out my window turned to darkness. Such are the after–effects of general anesthesia and, upon reflection, quite fascinating.

Beyond all else, however, I remember being comfortable after my first operation. Sure, the Demerol helped, but I was quickly able to space the injections to six hours and then eight (by the second day of recovery). My parents, being as wonderful as they were (and Dad still is), arranged for a private nurse to watch over me the first few nights. I recall this particular lady being a huge hockey fan and spending overnight hours immersed in the 1975 book My Three Hockey Players by the late Colleen Howe – Gordie’s wife; Mark and Marty’s mother. The nurse was a liaison between me and the hospital staff — and, as I recall, very attentive.

No matter the length of a surgical scar, or its location, nurses are going to get you up out of bed long before you feel any such desire. It is done not to torture a patient but to help allay pulmonary complications (i.e. pneumonia) from general anesthesia and blood clots that can form after invasive surgery. Thankfully, this is done with abundant patience and understanding (you wouldn’t want Bob Corran to be your nurse).

There is a technique to propping up oneself after a stomach operation. You hold a pillow tightly to the wound, roll onto your side and gradually use your arm and elbow to rise into a sitting position. For the first few days, you are winded upon accomplishing this — remember, abdominal muscles have been severed; clamped apart for three hours and then reconnected. Nurses and/or relatives will flank and help lift you into a standing position. The first couple of times, you may feel like passing out, though you almost never will. If you have an abdominal wound, chances are warm liquid will cascade down your legs and onto the floor. It’s a peculiar feeling though nothing to be concerned about. The collections of fluid that form after surgery in the abdomen are called seromas — pockets of serum or lymph produced at the site of any injury to the body (like when you get a blister). If there is a nine or ten–inch gash beneath your stomach wall, this production shifts into over–drive.

As a result, surgical drains are often left in place for several days. These are rubber tubes the circumference of a dime and often seven or eight inches in length. The first six inches are buried deep in the wound and seroma fluid is expelled through the one inch stitched into place above the skin. I remember being startled at how long the damned thing was when I had it removed.

By the third day after surgery, moving around becomes far–less burdensome. Fiery pain from the wound subsides, not unlike the scalding discomfort in the immediate aftermath of a sunburn. This process accelerates the more you get on your feet and walk. It doesn’t eliminate the need for pain medicine, but it mitigates narcotic addiction and definitely expedites the recovery process. Injections of Demerol (in 1976) or Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) today are rather intoxicating — literally and figuratively. I remember my neighbor, Ralph Wolfe, coming to visit me one evening after my first operation. I had been injected with Demerol ten minutes earlier and was stoned out of my mind. All I wanted to do is close my eyes and “float.” I apologized profusely to Ralph, but asked him to leave (which still makes me laugh).

The surgical recovery ward at Toronto General in 1976 was in the Norman Urquhart wing overlooking University Ave., across from Mount Sinai Hospital. Dr. Langer was a frequent visitor in the immediate days after my operation. On the third or fourth day, I summoned the nerve to ask him exactly how much of my intestine he removed.

“Oh, not a lot: Just about three feet of your small bowel and your ascending colon.”

“Not a lot!” I responded, and he laughed.

“Don’t worry, there’s more than enough plumbing left. You had some really bad inflammation and I had to take out a bit more than I initially figured. You’ll be back to normal before long.”

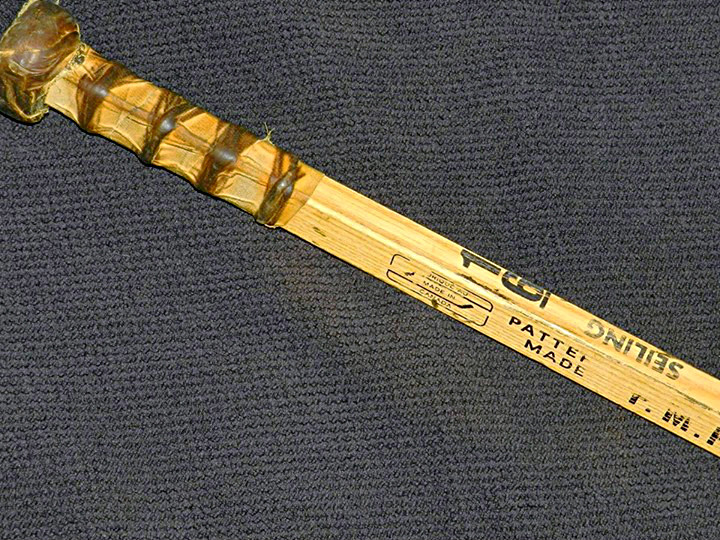

A few days later, I was watching TV in my room when someone knocked on the door and opened it. When the person came in, I did a double–take. It was veteran defenseman Rod Seiling of the Maple Leafs and he was carrying one of his hockey sticks.

“Hey, Howard, how ya doing today?” Seiling asked. “This is for you.” I took the stick and noticed it was signed by just about every player on the 1975–76 Leafs team: Darryl Sittler, Lanny McDonald, Borje Salming, Ian Turnbull, Dave (Tiger) Williams, coach Red Kelly… and, of course, Seiling, himself.

“Wow, this is incredible, Rod. Thank–you so much. But, how did you know I was in the hospital?”

He told me that Bob Davidson — a former Leafs captain and the club’s chief scout at the time — requested that he have the stick autographed. I found that strange because I had never met Bob Davidson. “That’s all I know,” shrugged Seiling.

He and I chatted for about 15 minutes. There was a playoff game that night and he had to get over to Maple Leaf Gardens — just down the street. I remember watching him play on TV a few hours later against Pittsburgh in the opener of a best–of–three preliminary round (Apr. 6, 1976). As it turned out, Bob Davidson was a patient of my uncle (Dad’s younger brother) Sheldon (a G–P), and he had asked Davidson if there was anything the Maple Leafs could do for me. Thus the visit from Rod Seiling and the autographed stick, which I covet to this day.

I was discharged from Toronto General on Thursday, Apr. 8, 1976.

A glorious moment in my life.

EMAIL: HOWARDLBERGER@GMAIL.COM

A very well told story Howard. That was a very difficult experience for a young person to endure. I loved the stories about your family relationships. You have A LOT to be grateful for and proud of.

As successful and well suited you are for your new career, your talent as a writer makes me wish you were still writing a regular column and/or on the radio. Both mediums are poorer for your absence.

This was a very interesting and moving story. Your memory is very impressive!

That must’ve been quite the thrill to get a signed hockey stick. When I was 12 or 13 I spent a week in hospital and I recall my friends mom bringing me two Dairy Queen Sundaes after she got off work one day. A very small gesture but the little things can make a big impact because I still remember how happy that made me.

I am sorry you suffered so greatly as a young person but I hope your story may help people today who are suffering from similar symptoms. My wife (Dana Tobe) read your story, and started telling me about your mutual family members. You had amazing parents, may your father live to 120. We all wish you nothing but the best of health – you and your two kids.

awesome story……it brought tears to my eyes. Your parents sound like super-parents.